It used to be missiles; now it’s oil, but Cuba is still in crisis. Back in ’62 the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis triggered a 13-day stand-off between the United States and the Soviet Union when the latter decided to ship ballistic missiles to Cuba. Fast

It used to be missiles; now it’s oil, but Cuba is still in crisis. Back in ’62 the so-called Cuban Missile Crisis triggered a 13-day stand-off between the United States and the Soviet Union when the latter decided to ship ballistic missiles to Cuba. Fast

forward 56 years to 2018 and the threat of a nuclear war may have receded, but war of another kind has rekindled crisis in the Caribbean.

Oil, more specifically Russian oil, is threatening not just a regional trade war, but one with global economic as well as political ramifications. It started just before Christmas in 2017 with a low-key, but nevertheless deliberately publicised meeting between Cuban ruler Raúl Castro and the head of Russia’s state-owned Rosneft oil company Igor Sechin.

Few details of the meeting in mid December have been released, but speculation was and remains rife. It is now reported by industry experts that Rosneft will take, or has already taken, a hefty stake in a major refinery in the central south-coastal Cuban town of Cienfuegos. The stake was previously owned by Venezuela, whose former leader Hugo Chávez was a close ally of Cuba’s Fidel Castro.

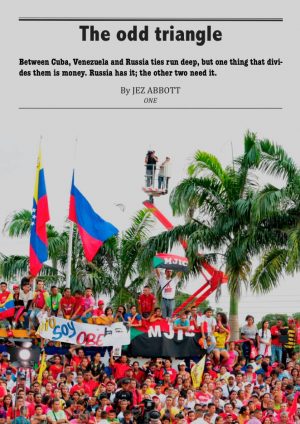

Unlike the crisis, Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro are dead. The drama however is being played out by their successors: president Nicolás Maduro and Fidel’s brother Raúl Castro. All three nations are tied not just by oil but an ideology rooted in revolutionary socialism. Maduro said in a speech celebrating last year’s 100-year anniversary of the Russian revolution: “This is your people, Lenin.”

Russia’s response was no less theatrically staunch or politically emotive: Rosneft commissioned a six-metre-high granite statue of the former Venezuelan president, installed in Chavez’s hometown Sabaneta. Addressing the crowd in Spanish Igor Sechin said at the unveiling of the Russian granite figure: “Russia and Venezuela, together forever!”

These ties run deep, but one thing that divides Russia from Cuba and Venezuela is money. Russia has it; the other two need it. The superpower has lent Venezuela billions to keep afloat a like-minded socialist regime mired in poverty. Much of this lending is through loans to the south American nation’s state-run oil company PDVSA. Instead of repaying in cash, it pays in oil.

This is then resold by the Russians to the tune of an estimated 225,000 barrels a day. Venezuela’s political and economic crisis, combined with Cuba’s desperate need for foreign investment, has given Russia a stronger foothold in Latin America creating tensions – tensions with unsettling echoes of the missile stand-off of ’62. America and its ultra-conservative president are not happy.

“There’s no doubt in my mind,” Arizona’s die-hard Republican Trent Franks told the American press, “that Russia has brazenly used the geopolitics of oil, directly propping up of regimes that are antithetical to the United States. They have literally used oil as a strategic weapon.” Oklahoma Republican Tom Cole agrees, saying Russian policy is largely defined be antagonising the USA.

It could go horribly wrong for almost everyone. Russia, like Venezuela, is struggling with international sanctions. Meanwhile the refinery in Cienfuegos, about 250km from Cuba’s capital Havana, is producing nowhere near its capacity of 65,000 barrels of crude daily, according to local press reports. Venezuela’s troubles have forced Caracas to cut oil shipments to Cuba that in the heyday and lifetime of Hugo Chávez amounted to 100,000.

The refinery is now processing only about 24,000 barrels per day, with the Russian state company Rosneft picking up the slack. Yet investing in an economy tottering on the edge of collapse is a high-risk strategy and counter to virtually all economic tenets. All of this is happening in the backyard of the USA, something president Donald Trump is watching with mounting alarm.

It’s an alarm made worse by Trump himself. The president has become increasingly hostile to Cuba and bent on undoing much of the bridge building undertaken by his arch-enemy and predecessor Barack Obama. New regulations announced last November, for example, ban Americans from any direct financial transactions with 180 entities tied to the Cuban security services.

Yet while the tensions grow between the US under Donald Trump and Cuba, countries like Russia are all too willing to fill the diplomatic, economic and energy gaps along with others such as China and Iran. Oil has emerged as perhaps the most “powerful counterweight to US political and economic statecraft, with the effect of undercutting US objectives in a way that’s alarming policymakers and members of congress”, according to US current affairs channel Vice News.

Responding to the Cuba-Russia oil deal US senator Patrick Leahy admitted Trump’s bid to clamp an iron grip on Cuba with sanctions was leaving “a gaping vacuum” for more hostile nations to fill. “The Kremlin has again become the island’s saviour amid a Cuban energy crisis caused by chaos in Venezuela,” Leahy wrote in an editorial. “This alone should set off alarm bells in the White House.”

So as Cuba takes steps to diversify the number of countries it buys oil from and sells its medical and other professional services, the changing nature of the Cuban-Venezuelan-Russian venture at the Cienfuegos refinery continues to capture press headlines and political attention.

Any energy agreement between Russia and Cuba is the result of a “financial triangulation” that also binds in Venezuela, reckons Jorge Piñón, director of the Center for International Energy and Environmental Policy at University of Texas at Austin.

The unfolding crisis of this triangulation is as fresh as the 13-day Cuban Missile Crisis is distant. But the dynamics and the dramatics are startlingly similar – days of international tension, petulant diplomatic posturing and icy political stand-off. Only the outcome of one – eventual resolution – could be wildly different from the other.

Jez Abbott