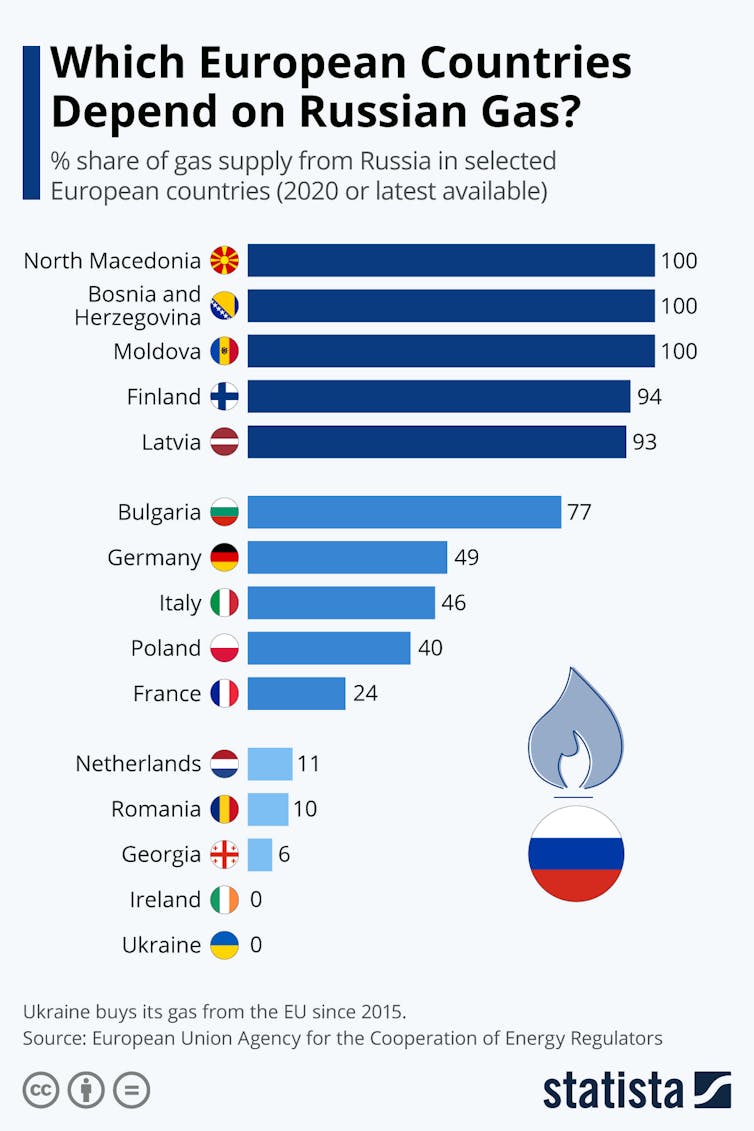

Russian energy giant Gazprom has completely cut off gas supplies to Poland and Bulgaria. Both countries are apparently being punished for refusing Russia’s demand that they pay for their gas in roubles.

Other EU countries have also refused to pay in Russian currency (doing so would provide a boost to the Russian economy), but so far only Bulgaria and Poland have had their supply cut.

The immediate response from Poland has been that it can “manage” without Russian gas, with storage levels high and demand decreasing as the weather gets warmer. Bulgaria meanwhile, has accused Gazprom of a serious breach of contract, and is in talks with EU allies about maintaining supplies.

It will not be easy. For while Bulgaria can gradually switch away from Russian gas and oil, an abrupt halt will cause serious worries. Alternative supplies from the likes of Azerbaijan will not be enough.

In the longer term, one option is to continue with the (currently abandoned) completion of Bulgaria’s second nuclear power plant near the town of Belene on the south bank of the Danube river. Along with Poland, Germany and the rest of the EU, Bulgaria will also look to increase its reliance on Norway, the Middle East and north Africa. And there will be calls across the EU to speed up a switch to renewable energy sources such as solar and wind power.

All of these moves will do serious harm to Russia’s economy. So why is it turning off the taps? And why is it targeting these two countries in particular?

We can make a decent guess that the main motive is to cause economic difficulty and political division in Poland and Bulgaria, and to challenge their support for Ukraine. Vladimir Putin will no doubt enjoy treating this as an opportunity to antagonise both Nato and the EU.

Historically, Russia also has form in seeking to undermine the economic and political independence of these two countries. A pact between the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany in 1939 denied the very existence of a Polish nation, and aimed to share its land. Similarly, Russia’s policy towards Bulgaria for over 100 years has been geared towards political, cultural and economic dominance.

By cutting off gas supplies, Russia has landed its latest economic blow against Poland and Bulgaria. But with international support, it is a blow that can be withstood.

Statista

My own economic research into social learning suggests that people, as well as business and wider societies, continually adapt positively to evolving situations.

Part of my research involved developing an economic model which shows how populations react to economic incentives and pressures, and how this is influenced by their historic experiences.

Evolutionary economics

I also examined the link between how economic incentives (such as perceived costs and benefits) and social preferences played a role in the rise and fall of communism. Put simply, we concluded that for thousands of years, human societies have evolved economically by experimenting and learning about their environment. They have become adept at responding to how it functions and changes, sometimes gradually, sometimes abruptly.

Applied to the situation today, the key message is that EU countries will eventually adapt to making a switch away from heavy dependence on Russian energy. This will be costly in the short run, but viable and beneficial in the long run.

So while there will undoubtedly be energy shortages caused by Russia using gas as what the president of the European Commission described as an “unjustified and unacceptable … instrument of blackmail”, in the long term, everything can change with new suppliers and alternative sources.

Poland and Bulgaria are no longer obedient vassals of Russia. And while they will both suffer difficulties and division, they can rely on the economic support of the wealthy countries around them. Wars are ultimately won by countries who can survive hardships in an organised way, and whose economies are not brought to breaking point.

The democratic societies of the EU and Nato, for whom freedom is an essential human value that needs to be protected, must stay united and help each other overcome Russian extortion. Luckily, human beings and most nations value freedom highly – even if it comes with a high economic price to pay.![]()

Alexander Mihailov, Associate Professor in Economics, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.