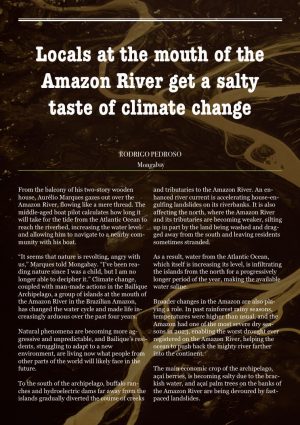

From the balcony of his two-story wooden house, Aurélio Marques gazes out over the Amazon River, flowing like a mere thread. The middle-aged boat pilot calculates how long it will take for the tide from the Atlantic Ocean to reach the riverbed, increasing the water level and allowing him to navigate to a nearby community with his boat.

From the balcony of his two-story wooden house, Aurélio Marques gazes out over the Amazon River, flowing like a mere thread. The middle-aged boat pilot calculates how long it will take for the tide from the Atlantic Ocean to reach the riverbed, increasing the water level and allowing him to navigate to a nearby community with his boat.

“It seems that nature is revolting, angry with us,” Marques told Mongabay. “I’ve been reading nature since I was a child, but I am no longer able to decipher it.” Climate change, coupled with man-made actions in the Bailique Archipelago, a group of islands at the mouth of the Amazon River in the Brazilian Amazon, has changed the water cycle and made life increasingly arduous over the past four years. Natural phenomena are becoming more aggressive and unpredictable, and Bailique’s residents, struggling to adapt to a new environment, are living now what people from other parts of the world will likely face in the future.

To the south of the archipelago, buffalo ranches and hydroelectric dams far away from the islands gradually diverted the course of creeks and tributaries to the Amazon River. An enhanced river current is accelerating house-engulfing landslides on its riverbanks. It is also affecting the north, where the Amazon River and its tributaries are becoming weaker, silting up in part by the land being washed and dragged away from the south and leaving residents sometimes stranded.

As a result, water from the Atlantic Ocean, which itself is increasing its level, is infiltrating the islands from the north for a progressively longer period of the year, making the available water saline.

Broader changes in the Amazon are also playing a role. In past rainforest rainy seasons, temperatures were higher than usual, and the Amazon had one of the most severe dry seasons in 2023, enabling the worst drought ever registered on the Amazon River, helping the ocean to push back the mighty river farther into the continent.

The main economic crop of the archipelago, açaí berries, is becoming salty due to the brackish water, and açaí palm trees on the banks of the Amazon River are being devoured by fast-paced landslides.

Meanwhile, the Amapá state government and the municipality of Macapá, the state’s capital that manages Bailique, are unable to mitigate the effects of the environmental changes, which have driven part of the population out of the archipelago.

Amapá’s government estimated last year that roughly 13,000 people were living along the archipelago’s eight islands, about 180 km (111.8 miles) and a 12-hour boat ride from Macapá. However, Brazil’s official census from 2023 registered no more than 7,300 people living in Bailique.

“There’s a lot of attention on the Amazon Rainforest, but little about its coast, which stretches from the state of Maranhão to Venezuela, being one of the most dynamic ecosystems in the world in terms of sensitivity to change,” Valdenira Ferreira, a scholar from the Scientific Research Institute of Amapá State (IEPA) who has been researching Bailique for two decades, told Mongabay.

“We’re talking about one of the most vulnerable areas on the continent, but the government is looking in the dark. There are no measurements or data beyond the superficial to draw up plans to adapt to these changes that are becoming more common each year,” she said.

To the north: Wasps, drying rivers and salty waters

Aurelio Marques, the boat driver who was calculating when the seawater would enter the riverbed in front of Livramento, a community founded by his father in the middle of the last century, says Bailique’s residents are divided about what to do in this scenario. His children went off to study and work in Macapá, Amapá’s capital, but his elderly parents don’t want to leave the place.

At the end of 2023, when Mongabay visited the area, Livramento was isolated from the outside world for a few hours a day. No boats could enter or leave it because of the Amazon River’s drought, something that had never happened before — there are no roads to or into the archipelago.

The dilemma about staying or leaving is boosted by the recent decline in living conditions. The community of Filadélfia, farther north of Livramento, endured the last seven months of 2023 without “really heavy” rain, as the residents say, necessary to endure an increasingly salty water river period.

“We’ve learned to catch rainwater and filter it,” Francidalva Farias, a Filadélfia resident, told Mongabay while showing an improvised hose connecting her house roof rail to an open cistern covered with a blanket in her backyard. Almost every house in Bailique has three water tanks: one with saltwater, which they use for bathing and washing dishes, and two for fresh water, used for drinking and cooking.

“We use the first tank as a filter,” Farias said. “When the dirt settles, we move it to the second one, which we can use to drink and cook. Because [the water from the river] is getting saltier and saltier. If it doesn’t rain, we have no water to drink.”

Walking around her community, a dozen sparse wooden houses connected by wooden walkways, Farias said she had never seen so many changes at the same time in the region, now heavily dependent on supplies from outside.

In December, only small boats, for a few hours a day, managed to navigate the low level of the river to get to the community. Due to the above-average heat registered in past winters, when rain was scarce, wasps became more aggressive, stinging residents more often and multiplying faster, to the point where they formed several colonies at the community’s school.

“Going to school is becoming dangerous [due to the wasps]. And we have to save potable water as much as we can. When we bathe in saltwater, we get itchy. Children get mild burns [due to the saltwater]. The clothes have to be dried soon; otherwise, they smell bad. And the soap doesn’t lather like in the freshwater; it’s weird,” Farias said.

Some families manage to buy potable water from Macapá, but others have to go through the salinization of the water period — it has been up to eight months a year in the north of the archipelago — exclusively with the water collected from rain. When it runs out, they have no choice but to drink the salty water.

“Saltwater intrusion is happening all along the mouth of the Amazon River, as is coastal erosion,” Ferreira said. “Both have to do with rising sea levels and changes in the Amazon River Basin. If the discharge of water at the mouth decreases, the sea advances further. If sediment loads increase along the rivers due to deforestation, for example, more dirt is carried to the Amazon’s mouth, which in turn increases siltation.”

Diseases and governmental negligence

Luiz Velázquez Tito, a Cuban doctor who worked in seven countries before settling in Brazil, reports that diarrhea, skin diseases and parasites are the most common health issues in the archipelago.

Tito arrived in the north of the islands in the middle of last year and, living in a room in a wooden house with no home appliances or even a bed, complains that the state government and Macapá City Hall have not offered him a suitable health structure or basic medicine. Tito is the first doctor to work in the north in eight years.

“They threw me here and left,” he told Mongabay while sitting on a worn-out plastic chair, the only furniture in his house. “I work in a room where I had to improvise a curtain as a wall between the triage, patients waiting and my medical care. I’ve worked in Angola, Venezuela and Haiti, but this is the place with the most adverse working conditions. I’ve never seen so many recurring problems, especially because of the water,” Tito said.

The salinization of the archipelago’s waters once was a rare phenomenon restricted to the north of the islands, the elders who spoke with Mongabay recalled, happening once every few decades as a result of a severe drought in the Amazon River.

The deforestation of the Amazon, the general temperature rise in the region and the warming of the oceans have made the cycle of floods and droughts of the world’s largest river increasingly extreme.

But Amapá’s Water and Sewage Company, responsible for Bailique water supply management, started dealing with the periodic salinization of the archipelago only in 2023 when it provided desalination plants in the archipelago’s main community of Vila Progresso. Developed for a different environment, it didn’t work due to the level of saltiness and sediments of Bailique’s water, greater than the machines were able to filter.

According to the company, a study is being carried out to measure the current level of salinization and residues. New plants, more suited to the local conditions, are expected to be placed in several communities by the end of the year.

Meanwhile, Macapá City Hall spent the second half of 2023 sending drinking water from the capital city in boatloads or in plastic bottles after declaring a state of emergency in the archipelago — which enables public officials to acquire services and goods with less bureaucracy and spending-proving control, among other things.

Some of Bailique families received nothing more than a pack with six 1.5-liter (0.4-gallon) bottles as boats stranded on riverbanks due to the drought.

The state government and Macapá’s mayor were questioned by Mongabay about the water supply, the abandonment of health facilities, and whether they have plans to mitigate the effects of changes in the archipelago’s environment but received no response.

Valdenira Ferreira and other experts of IEPA are awaiting funding from the federal government to carry out a continued measurement of Bailique’s salinization and erosion. The fund was promised in July 2023 by the Ministry of Integration and Regional Development, led by Waldez Góes, who ran Amapá as governor for four terms.

“We’ve got no response so far [about when the government will send funds]. We need research funding because the current policies for Bailique are being made without precise and continuous measurements. It is all being done within an emergency frame, but what we are seeing is that these phenomena won’t fade out in the upcoming years. Quite the contrary, actually,” said Ferreira.

To the south: Falling lands, swallowed houses

Like other residents, Erielson Pereira dos Santos doesn’t rely on government aid to survive. He lives with his family in a house on the banks of the Amazon River in the southern part of the archipelago. About a decade ago, he began sustainably managing açaí palm trees on his land.

Four years ago, however, the riverbank began to fall frequently, especially during the rainy season, taking away the palm trees and his livelihood with it. Just as Aurelio Marques looked at the dried-up river in front of his house, Santos sees his land being eaten away by a river with a stronger current day after day.

“I had 400 meters [1,312 feet] of planted açaí trees, counting from the riverbank into the island,” he told Mongabay. “Now I have less than 50 m [164 ft] left. By next year, all those açaí palms will be gone. And on top of that, the açaí berries will probably be salty on the next harvest, which didn’t happen on this part of the island before,” he said.

If the water is salty at harvest time, the açaí palm trees absorb the salt, changing the taste and making it harder to sell the crop. Santos is planting more açaí trees as far from the riverbank as he can, hoping that the landslide phenomenon will decrease its intensity over the next few years. Otherwise, he plans to leave for Macapá with his family.

Some institutes and universities in the region are trying to monitor the phenomenon, but there are few studies about the scale of what is happening in Bailique. A 2018 report from IEPA calculated that in some communities, erosion ate 10 m (32.8 ft) of land from the riverbank that year. Santos estimates that the yearly landslide in his plot is now four times larger.

Amazonbai, an açaí producers’ cooperative, has been helping riverine people since 2017 to sustainably manage the archipelago’s main economic activity. In 2022, they opened an açaí processing plant in Macapá and started to sell the industrialized organic açaí pulp to other parts of Brazil and the United States, England and France.

“We’re worried about these changes,” Amiraldo Picanço, president of Amazonbai agroindustry, told Mongabay by telephone. “We know that the ocean level is going to keep on rising, and it’s certainly going to push the river a little further in and that we will have more extreme drought and floods in the Amazon River. It’s a bit of a characteristic of the archipelago that the land falls in one place and appears in another, but what we have now is a maximized phenomenon combined with the pressure made by human activity.”

Buffalos and dams, a worsening scenario

About a 30-minute boat ride into the archipelago from the main community, a large river flows into the Amazon, resembling one of the many major tributaries of the world’s largest river.

It’s the Araguari River, which runs in parallel with the Amazon River farther north and has been suffering from siltation. A boom of buffalo ranches that were spared on Amapá’s mainland riverbanks in the past years, plus the construction of hydroelectric dams on the Araguari, damaged its flow to the Atlantic, creating a new course of water that runs to the Amazon River before getting into the sea.

Ten years ago, the Urucurituba River was a small creek feeding the mighty Amazon. Nowadays, it is a large and deep brownish river helping to accelerate land erosion in the south of the archipelago, according to experts and riverine people.

The greater the erosion, the faster the houses on the riverbank are falling down. Açaí farmer Erielson, for example, has already lost four houses in the last decade. A resident of the main village of Vila Progresso, with more than a thousand residents, said he has been living in his sixth house in the last eight years.

As the land falls, residents move what they can of their wooden houses farther into the islands, but many communities are starting to get cornered by private-owned buffalo ranches. Some villages are disappearing.

“How can you invest on this island if you know that you can lose your house?” boat pilot Aurelio Marques told Mongabay, assessing the increasing unpredictability of the environment at the “dancing waters” archipelago, as its residents sometimes call it. He takes another look at the river and estimates that the sea tide shouldn’t fill the riverbed in front of Livramento until dawn. The trip to the next community is postponed to the following day.

“I keep thinking: We’re surrounded by the biggest river in the world, but we have to bring drinking water from the capital or move around as nomads,” he said. “I’m going to wait for the next few years, but if it continues like this, I’m going to sell my boat. I wouldn’t like to, but I’ll have to leave.”

Rodrigo Pedroso

Originally published

by Mongabay

February 26, 2024