Germany’s coal exit commission has agreed on a proposal on how the country can manage to phase out its single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions by 2038, but the ensuing political decision-making process has only just started. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government coalition has to decide how to implement the non-binding proposal and draft necessary legislation. Many details have yet to be worked out and ultimately decided by parliamentarians in a process that could last well into 2020. In this factsheet, Clean Energy Wire lays out the basics of the ongoing political process to put the German coal exit into action. [Update adds details from economy ministry schedule on coal exit legislation]

Government must put proposal into action

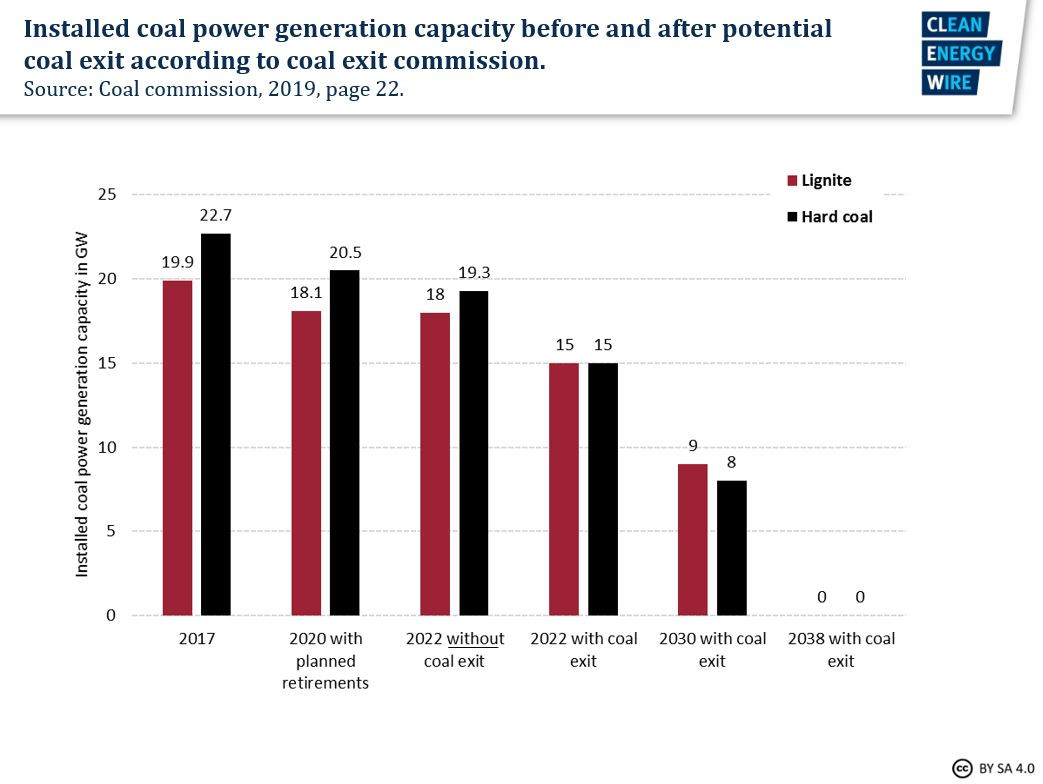

In late January 2019, Germany’s coal exit commission agreed on its highly anticipated phase-out proposal and recommended to end coal-fired power generation by 2038 at the latest. On almost 300 pages, the commission provided detailed suggestions on a wide range of aspects, but at the same time also omitted crucial questions – such as which power plant has to be switched off at what time. Policymakers now have to find an answer to these moot points if the commission’s carefully balanced phase-out plan is to be observed.

From the onset, the commission’s final report was meant to serve rather as a general blueprint for political decision-making than a detailed manual on how to proceed. However, according to the commission’s leadership, the proposal takes the interests of all main stakeholders into account, which is why it urges the government to follow its recommendations as closely as possible.

The structure of Germany’s federal political system brings with it that both the federal parliament (Bundestag) and the council of state governments (Bundesrat) have to give their consent to many aspects in the legislative process of a coal phase-out. [This factsheet gives a brief overview of German law-making on energy and climate issues.]

In the end, state governments will have to implement the coal exit at a regional level, for example through licensing future lignite mining projects or deciding which infrastructure investments are most pressing to give the regions an economic perspective that goes beyond coal.

Before parliamentarians get involved, however, the federal government first has to decide which details of the process it will adopt and draft relevant legislation for. Chancellor Angela Merkel’s government started by “closely and constructively reviewing” the final report, before saying in July that it will “rigorously implement the recommendations” of the commission. This process will eventually result in a set of energy laws before the end of the year, the government said.

The government presented a first set of key decisions on structural economic support of the coal regions in late May. It is working on a legislative draft it plans to decide in cabinet after the parliamentary summer recess. In parallel, the economy ministry is working on the actual coal exit legislation (see below).

Merkel herself has also signalled her readiness to move ahead with the deal regarding emissions reduction. “The fact that a commission made up from such different societal groups has found an agreement and created a framework is an important message for us. We will handle this very carefully,” she said. The deal showed “responsibility for society as a whole and we want to live up to it.”

Also the government coalition partner of Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance, the Social Democrats (SPD), said they are ready to implement the deal. Former SPD party leader Andrea Nahles in late March called for initiating the legislative process soon. “My expectation is that the (…) commission’s results will be implemented exactly as proposed,” Nahles said.

The coal exit is likely to also play an important role in the upcoming deliberations of Germany’s so-called climate cabinet, an intra-government panel announced in March that is supposed to bring all ministries relevant for climate action as well as the chancellor and government party leaders together in order to achieve progress on emissions reduction. It is also meant to serve as a platform to prepare the introduction of Germany’s highly anticipated Climate Action Law, which according to Merkel will be adopted before the end of 2019.

German politicians have called the coal exit‘s implementation “a very complex and unstable process” and warned that it “will surely not be a cakewalk”. Within the government coalition, conservatives from CDU/CSU have to agree with the SPD on the details of a phase-out. But state governments across the country are made up of much more varied coalitions, including many with Green Party participation.

In addition, several eastern German states head to the polls this autumn, including lignite mining states Saxony and Brandenburg. Both Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU alliance and the SPD have slumped in polls and in last year’s regional elections. Concerns that voters may perceive the deal proposed by the coal commission as a burden had made both parties nervous as the right-wing populist and anti-energy transition AfD party is polling strongly in eastern Germany. News of individual power plant closures in the economically weak eastern mining regions ahead of the autumn elections are feared to strengthen this trend. The government has said it will introduce a first draft of a coal exit law in autumn, which likely means after the elections.

Moreover, the state premiers of the three eastern German coal mining states, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Brandenburg announced that they are not going to pay for any structural economic adjustment measures associated with the coal exit from their own state budget. “By all means want to avoid the impression that the coal mining areas end up bearing the brunt” of a coal phase-out, the state premiers from the CDU and the SPD told chancellor Merkel in an open letter in early April.

The future process of implementing phase-out will be split up into two fields of action:

A. Structural economic change – support for lignite mining regions

B. Energy and climate policy legislation

Economy and energy minister Peter Altmaier said Germany will need two major laws to implement the phase-out plan. One on support for mining regions, the other on the timetable for coal-fired power plant shutdowns. However, several additional laws, amendments to existing legislation or regulatory changes, will likely be necessary.

A. Support for mining regions

From the beginning, the economic future of lignite mining regions was handled as key task of the coal exit commission, as reflected in its official title “Commission on Growth, Structural Change and Employment.”

The German government cabinet has decided first key points for coal region support and plans to get the necessary legislation on its way “quickly”. With the decision, the government aims to lay the groundwork that the coal regions “use the coal exit as an opportunity“ and “turn into modern energy and economic regions”, said economy minister Peter Altmaier. The key points include up to 40 billion euros in support payments by 2038 to strengthen local infrastructure and to create thousands of jobs through locating research institutions in former coal regions and incentivising private companies to invest there. The economy ministry plans to have the relevant legislation ready after the parliamentary summer break.

Against the backdrop of the autumn elections in eastern Germany, coal state premiers want to act quickly to present tangible negotiation achievements to their mining regions.

Newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung says that the government wants the coal states to finance part of the structural economic support measures for mining regions, as the states want to use 14 billion euros out the total 40 billion euros support package free of their own choice.

B. Energy and climate legislation

The implementation of the coal exit commission’s proposals for the energy sector will likely require the amendment of several existing laws, such as the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) or the Combined Heat and Power Law (KWKG).

However, the main piece of legislation will be a “hard coal exit law” draft, which will be turned into a “coal exit law” that includes lignite as well, once the government has finalised negotiations with lignite companies about the shutdown schedule and possible compensation payments.

The timetable for shutting down coal-fired power plants will be among the more contentious pieces of legislation, as individual regions, companies and jobs are immediately affected. The economy ministry has said it will present a first draft of the hard coal exit law in autumn. The final coal exit law, it said, can then be decided by the end of 2019.

The economy ministry said the decision on which hard coal plants are shut down first will be taken via tenders. “In the tenders, operators of coal-fired power plants can offer a price for the decommissioning of their power plants. Those who offer the lowest cost per CO₂ emission are awarded the contract,” it said.

It also said there was a general agreement with operator RWE that the first lignite shutdowns should happen with older plants in western Germany.

The opposition Green Party has published a ten-point-plan on how to proceed, including a timetable for closing the first coal-fired power plants.

In the beginning of May 2019, environmental NGOs Greenpeace and ClientEarth published their own proposal for a coal exit law, detailing a shut-down schedule. They criticised the government for failing to propose ways of implementing the official coal exit commission’s February 2019 recommendations.

A concrete plan for switching off individual power stations could also be decisive for whether or not the embattled Hambach Forest can remain intact or will be cut down by utility RWE to expand a nearby lignite mine.

On 20 February, North Rhine-Westphalia’s (NRW) state premier Armin Laschet said his government had agreed with energy company and western German lignite mine operator RWE on a moratorium for clearing the embattled Hambach Forest until autumn 2020. Laschet said preserving the Hambach Forest would be “desirable”, adding that the forest needed to be part of the negotiations between lignite companies and the federal government over which power plants to shut down when and how to compensate the operators. RWE has put the price tag for preserving the forest that has become a symbol for climate activists in the country at more than one billion euros.

The coal exit commission recommends settling questions related to compensation for operators of lignite plants as well as for employees in “mutual agreements.” First talks have already been conducted, as the question is closely interlinked with the decision on a timetable for taking power plants off the grid. RWE has said it estimates costs of 1.2 to 1.5 billion euros for each gigawatt (GW) of power plant capacity switched off.

However, the federal parliament’s research service in late February concluded that the German state is not necessarily liable to compensate coal plant operators. While compensation might be paid in certain cases of “otherwise unreasonable economic burden”, the proposal as it stands did not put any such burden on individual plants. In April, the government stated that “possible” compensation payments were still subject to the review procedure. In July, economy minister Peter Altmaier said he had the goal of finding a mutually agreeable solution with lignite companies. “The talks with RWE are advanced and very constructive.”

Should mutual agreements not be found by the 30 June 2020 deadline, the commission recommends settling the dispute “by regulatory law,” which would mean that the government decides which plant has to shut down when to provide planning security and ensure uninterrupted power supply.