The goal of climate neutrality by 2050 is still far, too far away. A brief reflection on the obstacle course we are facing today.

The goal of climate neutrality by 2050 is still far, too far away. A brief reflection on the obstacle course we are facing today.

The planet’s climate is sick. Scientific evidence clearly states that anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases are the main culprits of the disease, confirming what Swedish chemist and physicist Svante Arrhenius hypothesised as early as 1896, even before receiving the Nobel Prize. In the 800,000 years preceding the Industrial Revolution, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere fluctuated between 180 and 300 parts per million (ppm), causing an alternation between ice ages and relatively warm periods. But in just over 200 years, from the Industrial Revolution to the present day, the concentration has shot up to over 420 ppm due to the intensive use of fossil fuels: coal, oil and natural gas. With obvious effects on the climate.

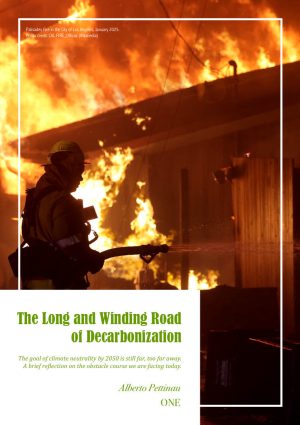

Effects that are not limited to temperature records (with 2024 replacing 2023 at the top of the worrying ranking of the hottest years ever). However, this extends to the increasingly frequent extreme weather phenomena we are called upon to witness. An example is given by the floods that hit the Valencia area at the end of October 2024, with 229 victims and damage estimated at around EUR 30 billion. Or the fires that devastated the city of Los Angeles in January of this year, with 25 victims and damages estimated at around 200 billion dollars. Nothing new, but it is the increasing frequency that is worrying.

This is why many countries, including the European Union, have adopted strategies to decarbonise their production systems, strategies for an energy transition aimed at achieving the so-called climate neutrality with net zero greenhouse gas emissions. Certainly not the first energy transition that mankind has faced, but the first, let’s say, against the trend.

A look back

Coal, oil and natural gas. It is precisely fossil fuels that drove the first real energy transition, which, with the Industrial Revolution, enabled a substantial change in the standard of living of millions of people. The evidence is given by the per capita gross domestic product of what we now call industrialised countries: it remained almost unchanged for nearly a thousand years, with very little prospect of growth and economic emancipation between one generation and the next but has soared since the 19th century thanks to the industrial revolution, leading us to the lifestyle we can afford today.

An energy transition born from below and driven by a direct and immediate economic return for investors. First, the steam engine, with the energy of coal, made production processes more profitable than those powered by the muscle power of men and animals (and only sometimes by the energy of water and wind). Then came internal combustion engines powered by oil and its derivatives, which in many cases supplanted coal being cheaper. And finally, natural gas, for many applications, is even cheaper than coal and oil. Decision-making processes started from the bottom, from individual companies, and were then transposed into the strategies and policies of many countries, with a so-called bottom-up approach.

The consequences of these transitions? Certainly, an increase in prosperity and greater prospects that new generations would have a better standard of living than their predecessors. In a word: ‘progress’. However, there is also an increasing economic disparity between developed countries and those lagging behind in these transitions (what many call ‘the great divergence’). And a steady increase in carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, with increasingly evident consequences for the planet’s climate.

A new transition, but in reverse

It is because of the intensification of these extreme events, caused by the increase in the concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, that a new energy transition is necessary and increasingly urgent. This time, it is aimed not at improving profits but at containing greenhouse gas emissions and carbon dioxide. This is the key problem: if previous energy transitions led to a direct economic advantage for those investing in new technologies, the transition needed to combat global warming requires huge investments and higher production costs. A process that, as a consequence, cannot start ‘from the bottom’, from single companies, but requires policies that incentivise or impose the necessary actions for sustainability. From the ‘bottom-up’ approach of previous energy transitions to the ‘top-down’ approach required for the green transition.

What are the brakes?

Governments are hesitant. Apart from a few token declarations or attempts of greenwashing, serious and substantial measures are mostly postponed. By rich countries in order not to compromise industrial competitiveness; by developing countries – typically more exposed to climate consequences – in order not to give up their limited opportunities for economic growth. Energy transition means guaranteeing huge investments, insufficient if other countries do not adopt similar ones, the results of which will only be visible in many decades. It is totally unacceptable, according to the logic of votes.

Today, unfortunately, there is still a lack of expertise and sensitivity on energy issues at all levels, from policymakers to the population. The cause is the general lack of interest but also the circulation of distorted and misleading information, which tends, on the one hand, to underestimate the problem and, on the other, to present miraculous and simplistic solutions to a problem that is extremely complex, requiring coordination and cooperation between people, companies, nations. Coordination and cooperation are where today’s approach is represented by concepts like ‘not my business’ or by election slogans such as ‘America first’ (declined in similar ways by most national governments).

Yet the solutions are there

Information and cooperation. These must be the first step for a true energy transition. Information at all levels, from the major decision-makers to the population, who must make increasingly conscious choices not only when they go to vote, but in their everyday behaviour (the conscious use of energy is always the most effective of all energy transition measures). Many of the technologies are already mature or at a high readiness level. Reducing waste, increasing efficiency, exploiting renewable energy sources (solar and wind, but also hydroelectric, geothermal and biomass), developing efficient and reliable energy storage systems, replacing fossil fuels with renewable fuels in the hard-to-abate sectors and, in the short to medium term, the new generation nuclear energy power plants. However, only greater awareness and responsibility at all levels will lead to virtuous behaviour by governments, companies, and individuals and to a recovery of the original idea of sustainability based on the three traditional pillars: environmental, economic, and social.

The only possible way to achieve a sustainable transition is to adopt global, far-sighted, and flexible strategies that are easily adaptable to future developments in technologies and markets. And socially just, with the richest countries (the big culprits of the climate crisis) having to shoulder most of the economic burden of the transition, which is unsustainable for developing countries if left alone.

A winding road

This is still too difficult to accept: today, it seems we are going in the opposite direction, with priority being given to the immediate interests of individuals, companies (primarily the large multinationals), and nations. And competition is still on products, not on technologies: on the global market, those who produce goods at lower costs prevail, not those who develop more sustainable technologies. How many more Valencias and how many more Los Angeles will it take for people to start taking a stand and deny the vote to those who do not undertake truly green policies? How many lives and how many billions of dollars are still to be paid for ‘not my business’ to become ‘everybody’s business’? That it is everyone’s business is well known: every tonne of CO2 we emit today is estimated to cause, in the present and near future, damage to society of around 300 dollars. Avoiding its emission would only cost a few tens of dollars, but it is easier to think about today than tomorrow and bury our heads in the sand.

We are facing a ‘long and winding road’, the only road available, which to be travelled requires the ‘greenest’ of all fuels, but probably the most difficult to produce: a mixture of knowledge and cooperation.

Alberto Pettinau