In most countries today, a minority of people have ever heard of carbon capture and storage, and still fewer have much knowledge of how this seemingly outlandish idea of stashing our CO2 emissions underground might actually work.

In most countries today, a minority of people have ever heard of carbon capture and storage, and still fewer have much knowledge of how this seemingly outlandish idea of stashing our CO2 emissions underground might actually work.

Yet from 2008 to 2010, so-called ‘CCS’ was thrust into the limelight in the Netherlands and parts of Germany as large sections of the public came out passionately against the use of the technology in their regions, fearing dangerous CO2 leaks, contamination of farm land, or even earthquakes. Backed by some environmental groups such as Greenpeace, local activist groups were formed, petitions signed and large protests held.

In Germany, CCS opponents employed strikingly effective imagery of timebombs and gas masks, and drew analogies with the equally emotive issue of nuclear waste disposal. With unfavourable media coverage also growing, CCS rapidly became a toxic political issue, and politicians were quick to distance themselves from the technology in the run up to local and national elections. The end result was effective moratoriums on onshore storage of CO2 in both countries, and a resounding victory for citizen activism.

The fossil fuel and energy companies behind these early CCS projects in Europe were poorly prepared for such a response, as the technology was not at first regarded as particularly controversial. Underground storage of other industrial gases is relatively common, and as a climate mitigation technology CCS also had the backing of many environmental groups and respected research institutes.

Considering most of the technology involved in the process as straightforward and risk free, the project developers saw little need for much consultation with local communities beyond the bare minimum required by permitting law. As we now know, the state of public opinion on CCS was in fact much more fragile. New technologies are always subject to greater scrutiny than well-established ones, and the novelty of CCS at the time was highlighted by the fact that EU member states were then still in the process of implementing various regulations to govern the new projects.

Probably most importantly, the idea of storing CO2 emissions within the earth is fundamentally unappealing, and is often instinctively viewed as a quick and unsustainable fix for fossil fuel companies to continue ‘business as usual’ rather than properly addressing the problem by stopping CO2 emissions

altogether.

While many of the initial concerns about CCS were driven by fears of damaging or dangerous local effects of a CO2 leak, this somewhat uncertain status as a ‘proper’ climate change mitigation strategy has undoubtedly contributed more to mobilising opposition, and has led to the involvement of some influential environmental groups who see it as an unwelcome distraction from the development of alternative climate solutions.

Although other CCS projects around this time were seeing little opposition or even active support in other countries such as the USA, Australia, and Spain, these negative experiences in the Netherlands and Germany would fundamentally change the approach the emerging CCS industry took towards public communications.

Most projects since have made use of dedicated ‘outreach’ teams with trained communication specialists, and sought above all to develop more trusting relationships with local authorities and members of the public from as early on as possible. As large fossil fuel and energy companies are not generally perceived as acting in the best interests of either the environment or the public, this can be challenging, and the help of more trusted organisations such as research institutes and NGOs can be hugely important in winning support.

Above all, local communities need to feel that they are being listened to and can have some impact on the process, so feedback is carefully collected and taken into account wherever possible. In the place of formal presentations to large groups of people, the industry has moved towards more informal ‘exhibit style’ meetings and house visits which allow one-to-one communication and prevent a few vocal opponents from swaying a crowd. Companies have also tried to emphasise potential benefits for the community as much as explaining the risks, including employment opportunities, local investment, and international prestige.

While many of these ideas may seem like common sense, and are not new for other, more controversial industries like chemical plants and nuclear power, the CCS industry has faced some unique challenges in developing its communication strategy.

Most people encounter the technology for the first time when a project is planned near their community, so communicators need to start with the basics. This usually includes presenting the evidence for man-made climate change, and making the case for why CCS needs to be part of a solution, often with reference to the country’s current energy supply and how the technology can complement other measures such as renewable energy and improving energy efficiency.

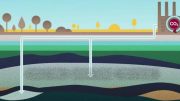

The nature and properties of CO2 also needs to be discussed, as some people tend to mistakenly identify it as a toxic or even explosive gas. Public understanding of how CO2 is actually stored is limited, with ideas of large underground caverns of the gas, not far below the surface, helping stoke fears that it could easily escape. In reality, CO2 is soaked into the pores of rocks several kilometres down, and prevented from surfacing by layers of impermeable rock above. Using real samples of these rocks and to-scale diagrams of the depth of the storage location have proved essential in getting across the key idea that a CO2 leak is extremely unlikely.

As the developer stung by the mass public opposition in the Netherlands, oil company Shell have arguably done more than many to develop a comprehensive communications strategy for their more recent CCS projects.

Although eventually cancelled by the UK government, the company’s plans at Peterhead power plant in Scotland won widespread local support, and involved working closely with local schools and businesses, as well as an eye-catching nation-wide advertising campaign.

A similar approach was used for the successful Quest project in Alberta, Canada, which began operating in 2015, where the team would even show up at local cafes to talk informally about the plans over a coffee. While some of these more successful projects might be considered less controversial proposals than those which met with serious opposition, often involving putting the CO2 offshore, this is not always the case.

Even in Europe, plans for a new coal power plant with CCS in Spain eventually met with approval following the concerted communications efforts of a local research institute, despite the project ultimately being abandoned due to lack of funds.

Today, there is growing confidence within the CCS industry that projects can win local acceptance if enough care is taken, although there is also an understanding that the social context of some locations may not be suitable. However, with CCS going from strength to strength in North America, but still failing to take off in Europe, the memory of the Dutch and German experiences are proving difficult to banish entirely.

A relative absence of economic drivers and lack of infrastructure for the technology in Europe is the main reason for this contrast in fortunes, but there is a danger that the perceived unpopularity of CCS in the region is acting as a convenient political excuse to halt its development.

CCS is yet to find an equal place alongside renewable energy in the public and political debate around reducing CO2 emissions, despite organisations like International Panel on Climate Change and the International Energy Agency agreeing that it must form part of the solution, and it is clear that the battle for public opinion is far from won. The next frontier for CCS communication must go beyond local concerns and seek to make the case for technology at a national and international level.

Toby Lockwood