The veteran leftist has promised deep social and economic reforms on decarbonisation and climate adaptation as president, but faces challenges in testing times

Colombia’s first ever left-wing president, Gustavo Petro, took office this Sunday, 7 August, alongside Francia Márquez, the country’s first Afro-Colombian vice-president, after a 19 June election victory that saw them gain 11.2 million votes in a second-round run-off – the highest popular vote in Colombia’s history.

Petro and Márquez have promised a social transformation that will lead Colombia into an “era of peace”, with care for the environment cutting across all areas of their government. The aim of their administration, according to their published proposals, is to turn the country into a “world power of life”, seeking to “carry out fundamental transformations to face the emergency caused by climate change and the loss of biodiversity” – a process that would mean “leaving behind the dependence on the extractivist model and democratising the use of clean energies”.

Manuel Rodríguez Becerra, president of the National Environmental Forum and a former environment minister, told Diálogo Chino that “The new government is the most environmentalist in history”, pointing to several key figures who are experts in the field, starting with the president himself.

The new government is the most environmentalist in history

Rodríguez describes vice-president Márquez, a former Goldman Prize winner, as “a recognised socio-environmental leader”, and highlights that the new environment minister, Susana Muhamad, was in charge of the environment department for Bogotá during Gustavo Petro’s time as mayor of the capital (2012–2015).

Elsewhere, Rodríguez points out that the new agriculture minister, veteran Cecilia López Montaño, previously had a spell as environment minister in the 1990s, and claims that incoming finance minister, José Antonio Ocampo, is “one of the few in Latin America who has done in-depth research on sustainable development and the environment.”

The cabinet may be packed with sympathetic and more progressive heads, but realising progress on environmental issues will not be entirely straightforward for the Petro administration, which is likely to face a sharply divided parliament, impacts from global crises, and pushback from the country’s oil and gas industry.

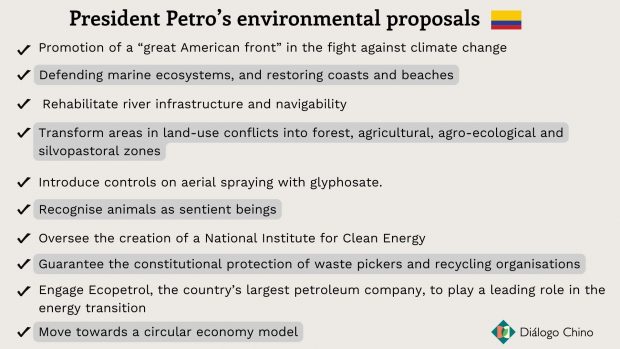

Petro’s environmental proposals

The new government faces two overriding challenges to achieving its economic transformation: the first is the promotion of a decarbonised economy, with the second a shift away from the country’s reliance on foreign production in favour of more local output.

Key to confronting this challenge of driving local productivity are issues of water governance and access, as the Petro government programme details, with water management also central to its ambition to make Colombia a “leader in the fight against climate change”. Petro has proposed a system of spatial planning around water, in which productive activities compatible with the protection of nature will be promoted; exactly what sort of activities these are is not made clear.

There are also promises to protect water sources, including in the country’s river basins, páramo moorlands and aquifers, with increased control for environmental authorities. The president has also pledged to ensure universal access to the minimum vital water supply as a fundamental right and common good – a promise that Petro managed to fulfil during his time as mayor of Bogotá, though not without criticism.

According to Manuel Rodríguez, the main environmental challenge facing Colombia is deforestation. The latest WWF report, Colombia has two of the world’s 24 “fronts” most affected by deforestation, including in its Amazon region, which in 2020 lost more than 109,000 hectares of forest, according to the Bogotá-based Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies (IDEAM).

To confront forest loss, the Petro government programme states that it will promote the development of agroforestry and silvopastoral systems, and the production and use of non-timber forest products, as well encouraging nature tourism under the leadership of community organisations. Illegal appropriation of land, activities related to drug trafficking and mining, it boldly claims, will be stopped, with particular focus on agricultural border areas.

Five decades of conflict Colombia has experienced more than 50 years of complex violent conflict involving the state, right-wing paramilitary groups, criminal gangs and revolutionary guerrillas, such as the demobilised FARC – whose splinter groups still operate – and the National Liberation Army, the last recognised guerrilla group.

Another notable issue with a bearing on the government’s sustainability agenda is the upholding and implementation of the country’s landmark peace agreement, signed with the FARC in 2016. This includes a comprehensive rural and agrarian reform that resolves inequality in land tenure – one of the main drivers of the long-running conflict. According to a study by Oxfam, based on the 2014 National Agricultural Census, the top 1% of large farms in Colombia own 81% of the land.

Petro and Márquez propose to move towards “closing the inequality gap” in land and water tenure, using agrarian and water reform to transform the countryside “in terms of production and social and environmental justice”. As part of this commitment, women will reportedly be given priority in land titling – reflective of the strong gender focus and prominence given to women in the Petro programme, with the proposal document’s very first chapter entitled “Change is with women”.

An allied and renewed congress

Things look to have got off to a good start. To stand a chance of carrying out this ambitious package of reforms, the government has already taken on the task of coalition building to achieve a majority of seats in the Colombian congress, an otherwise divided chamber. In addition to the Pacto Histórico – the coalition of parties that supported Petro’s candidacy, which has also built a majority in the senate – the president has received the support of other parties that had previously opposed his ideas, such as the Liberal, Conservative, Union Party for the People and Green Alliance, among others. For his supporters, this alliance shows the government’s conciliatory attitude – but for the opposition it is a sign that Petro is willing to “sell his soul to the devil” in order to implement his programme, phrasing used by various critics in recent month.

The new congress, which took its seats on 20 July, has also seen a renewal for Colombian politics, as 181 of the 296 legislators are entering the house for the first time, with many of them coming from social and feminist movements, indigenous groups, Afro-descendant backgrounds, as well as recognised environmental and animal rights leaders.

The pro-government bench of senate has already made its influence felt barely a week after taking office, with the approval of the Escazú Agreement in its second debate, with 74 votes in favour and 22 against. For the Escazú Agreement – the landmark treaty seeking to protect environmental defence – to enter into force in Colombia, it needs to be approved in two more debates in the congress and then ratified by the president.

This approval would be crucial, considering that Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world for environmental defenders, according to the latest report by Global Witness, with 65 people reportedly killed in the country in 2020 for their environmental advocacy work. Meanwhile, the Bogotá-based Institute for Development and Peace Studies (INDEPAZ) has a list of more than 600 environmental leaders killed since the signing of the peace agreement in 2016. In its programme document, the Petro administration pledges to investigate the causes and perpetrators of environmental conflicts.

Unpopular energy proposals

Decarbonisation, including transforming Colombia’s energy mix, is the other major environmental objective of the new government, which has made bold proposals to move beyond a fossil-fuel economy dependent on profits from oil, coal and gas production. President Petro has said that the winding down of the extractivist model will be gradual, though this suggestion has still raised much concern, given that Colombia’s primary export is oil: in 2021 the state oil company Ecopetrol earned US$3.7 billion in profits, the highest figure in its history – and gas production is on the rise. Specifically, the government’s plan states that no new licences for hydrocarbon exploration will be granted, but that existing agreements will be respected.

Not even environmentalists such as Camilo Quintero, former undersecretary for the environment in the Medellín mayor’s office, see the wisdom of curbing production. “The energy transition must be fair and orderly so that by solving the environmental problem we are not creating other problems. There are public finances that need to be taken care of and that have partly financed social programmes,” he concludes.

Colombia cannot afford to lose its oil profits, and a section of the government coalition and the centrist parties that supported it agree

Manuel Rodríguez agrees: “Decarbonising the economy – that is, producing fewer greenhouse gases – is different to suspending the exploration and exploitation of hydrocarbons. If Colombia stops exporting, then another country will take over that market.”

President Petro also stated in his campaign that there will be no fracking during his administration, a decision backed by new environment minister Susana Muhamad. “We want to ban fracking in the Congress of the Republic and stop the licenses of pilot projects, which will be one of the first actions we will take as a government,” she told local news following her appointment in July.

This fracking announcement has generated concern in the hydrocarbons sector, as Ecopetrol currently has two pilot fracking projects in the preparation stage and two contracts in force with the National Hydrocarbons Agency to evaluate the impacts of this method of exploitation.

Some government representatives have made pains to nuance this proposal, such as the new finance minister José Antonio Ocampo, who said last month that Colombia should “explore more and look for more gas” – and that it should continue producing oil to be self-sufficient, and continue exporting or else “the balance of payments problem becomes unmanageable”.

Another obstacle for the new administration is a lack of money, which could prevent proposed goals from being achieved. The outgoing government of Iván Duque left a fiscal deficit of more than US$19 billion, the highest in Colombia’s history. Financial and energy problems are being aggravated by the global crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as Russia’s war on Ukraine.

Given this adverse situation, Mauricio Jaramillo, professor of political science at the Universidad del Rosario in Bogotá, believes that the energy transition will not be an easy process: “Given the lack of resources, Colombia cannot afford to lose its oil profits, and a section of the government coalition and the centrist parties that supported it agree on this, but if the energy transition is delayed, their bases may feel let down.”

Similarly, Jaramillo says, the business sector opposes the transition and the ban on fracking pilots, so we are likely to see constant tension within the government, a tricky balancing act between moving forward with changes to the energy mix at a pace that does not alarm the business sector but also does not disappoint the grassroots that elected it.

Originally published by Dialogochino