Chancellor Angela Merkel called the controversial carbon capture and storage (CCS) a potentially key element for the country’s efforts to tackle climate change. The country can only become climate-neutral by 2050 if it is willing to employ CCS to deal with unavoidable emissions, Merkel said in an interview with Süddeutsche Zeitung, published in cooperation with other major European newspapers, including the Guardian.

Chancellor Angela Merkel called the controversial carbon capture and storage (CCS) a potentially key element for the country’s efforts to tackle climate change. The country can only become climate-neutral by 2050 if it is willing to employ CCS to deal with unavoidable emissions, Merkel said in an interview with Süddeutsche Zeitung, published in cooperation with other major European newspapers, including the Guardian.

Several European countries have started an initiative aiming for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by mid-century. “I am firmly convinced that this can only be done if one is willing to capture and store CO₂. The countries in question do not deny this. The method is called CCS – and for many in Germany it is a highly charged term,” Merkel said.

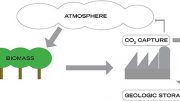

Until now, CCS – a technology that captures carbon emissions and stores them underground so they are not released into the atmosphere, where they contribute to climate change – has been off-limits in Germany because of public criticism over the involved costs and risks for the environment. Answering the question whether the CCS debate wasn’t already dead in Germany, Merkel said: “Now it is back.” The country needs a “wide debate in society” and CCS will also be on the agenda of her climate cabinet, she added.

A renewed public debate on the controversial technology looks set to become an uphill battle for Merkel’s government. While many researchers continue to point to a likely necessity of CCS, politicians have largely stayed away from the topic in recent years. Merkel’s remarks could be a first “test balloon” for a renewed debate, wrote Silke Kersting in an opinion piece in German business daily Handelsblatt about Merkel’s first mention of CCS at the Petersberg Climate Dialogue in Berlin. In what German media called “a nod” to French President Emmanuel Macron, the chancellor came out in her speech in support of a net-zero target, but said afforestation and CO₂ storage would be necessary. Her environment minister, Svenja Schulze (SPD), also said Germany needed to reopen the debate about carbon storage.

Other governments have been pushing ahead with research funding and pilot project support. Norway is developing plans to capture and store huge amounts of CO₂ from European neighbours in empty gas fields under the seabed off its North Sea coast. UK energy minister Claire Perry recently announced that her ambition was for her country to become a global technology leader in carbon capture.

The energy transition in Germany meanwhile is in full swing and the country aims to become largely greenhouse gas neutral by mid-century. The official goal is to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80 to 95 percent by 2050. Merkel’s call for Germany to now aim for net-zero emissions would imply an orientation towards the upper end of the corridor – something her environment minister has been advocating in her first draft for a climate protection act.

CCS is controversial because critics see it as an expensive technology that could ultimately perpetuate rather than reduce reliance on fossil fuels. In Germany, research and even some environmental NGOs support the idea of using carbon storage if it is not employed to extend coal and gas-fired power generation. In September of last year, an alliance of German experts from science, industry, government and environmental organisations called for an immediate and open public debate on whether and how carbon capture and utilisation (CCU) and storage (CCS) should be used as climate protection instruments for unavoidable industrial processes. At the moment, however, those technologies are still much too expensive, and a scale-up would require government support and the right regulations. German industry representatives have said that a higher price on CO₂ emissions is necessary for the technology to become a business case.

“Misguided” debate in Germany

For geological reasons, storage potentials in Germany are mostly under inhabited areas, not the ocean floor – which does little to dampen public criticism.

According to Erika Bellmann, climate and energy expert at environmental NGO WWF, the debate leading up to the technology’s earlier rejection was misguided. “It did not centre on small amounts of residual emissions in industry, but was essentially about saving coal-fired power generation and the fossil energy industry. That led to many misgivings which cannot be dispelled overnight,” Bellmann recently told Clean Energy Wire.

After strong public opposition, Germany introduced a law in 2012 that gives federal states a veto right regarding carbon storage on their land. Merkel’s administration dropped plans earlier this decade to support carbon capture amid voter protest. At its formation last year, her coalition agreed to consider limited CCS for industrial processes but declined to reconsider scaled-up plans to store poisonous emissions underground.

CCS has not featured in recent polls on the public’s acceptance of technologies needed as part of the energy transition because the subject has been widely seen as a no-go. Researchers at the Fraunhofer ISI institute concluded in an analysis of public acceptance published in 2015 that the technology has barely any support. “The results indicate that Germany’s citizens assess CCS as a high risk technology and do not perceive its benefits,” they wrote.

In a survey in 2011, 59 percent said they would be concerned or very concerned should a CO2-storage facility open within a 5 km radius of their home; 18 percent said they would not be concerned very much, while only six percent said they would not be concerned at all.

Mixed reactions by German government and opposition politicians

Members of the German federal parliament are split on the issue. Replying to questions by Clean Energy Wire, Georg Nüßlein – deputy parliamentary group head of Merkel’s conservative coalition partner CSU – said Germany should now focus the “here and now” and implement climate action measures to reach 2030 targets, such as a tax bonus for energy-efficient building modernisation. “Apart from that, we believe that CCS is an outdated technology if we manage to establish a circular CO₂ economy. If we manage to create intelligent CO₂ cycles, this will benefit the climate and help to conserve resources in the economy,” he said.

Joachim Pfeiffer from Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) said the fact Germany has a “de facto ban” on CCS is a “technological and climate policy mistake”. CCS and CCU could be “an important contribution to reaching climate targets” and deal with unavoidable industry emissions, he told CLEW. “If we do not want to deindustrialise Germany and at the same time take our climate protection goals seriously, we cannot give up these technologies in the long term.”

Lisa Badum, climate policy spokesperson of the Green group, told Clean Energy Wire that Merkel bringing CCS back into the debate gave reason to suspect that the chancellor aims to “camouflage climate policy inaction”. Badum said there was currently no profitable pilot project in Germany, and all federal states with suitable geological conditions had adopted parliamentary resolutions that reject CCS on their land. “This has also been done with the Union’s (CDU/CSU) consent. The debate around CCS therefore has ended a long time ago.”

“The Green Party is open to all technological solutions for climate action. However, the following conditions have to be met: technically feasible, safe, economically sound and accepted by the population. CCS meets none of these criteria. That’s why it’s factually dead in Germany.”

Lukas Köhler from the business-friendly Free Democratic Party voiced support for the use of carbon capture. “We want to make it possible to use CCS for unavoidable industry process emissions,” he told Clean Energy Wire. “However, the FDP rejects CCS for the energy industry, as there are emissions-free alternatives for this sector. In general, we prefer avoiding CO2 emissions altogether, but storing is still better than emitting.” Köhler also called for adjusting the legal framework. “In particular, we have to do away with the deadline for applying for new CO₂ storages that ended in late 2016.”

Left Party politician Lorenz Gösta Beutin rejected the technology outright. “CCS is a risky technology which does not solve problems, but creates new ones – an expensive and dangerous dead end.” Reducing emissions by 95 percent by 2050 was possible without the technology, as shown by an UBA study. Beutin welcomed the current laws. “Still, a ban on CCS would send a clearer message.”

The need for CCS, and warnings of potential risks

Energy and climate scientists say CCS will likely be needed in the future. While emissions in the energy sector could be reduced to zero with renewable sources, some emissions from industrial processes or in agriculture will be unavoidable in the long term.

The scenarios to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees presented by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in their latest report also included some form of CCS, said Sabine Fuss, researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC).

“That’s not to replace the reduction of emissions,” she stressed. Measures such as direct CO2 capture or the form combining bio-energy and capture (BECCS) will be necessary on top of efforts to cut emissions in order to get CO2 that has been already emitted out of the atmosphere. “In a way it’s a sign that we are already late.”

Fuss said that other countries like Switzerland or Norway invested in the technology, potentially putting Germany on the back foot. “We cannot afford to not talk about such technologies,” she said. “Whether they will be deployed in Germany itself is a different matter.”

The UK’s Committee on Climate Change (CCC) stated that “CCS is a necessity not an option” for reaching net-zero emissions in its report from early May, which called on the government to aim for climate neutrality. Studies on the future of the German energy system see an increased use of CCS the more ambitious the greenhouse gas reduction target is set in the scenarios.

The Federation of German Industries (BDI), Germany’s powerful industry lobby, said in its landmark study on possible paths to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the economy that reaching the upper 95-percent-reduction goal would require exponentially larger sums of investments and the use of “currently unpopular technologies such as CCS,” particularly in tackling industry emissions.

However, the BDI also calls CCS “non-sustainable” in the long run, stressing the need for new game-changing technologies and pointing to hefty resistance. Scenarios in other studies do not rely on CCS at all for a 100-percent renewable global energy system.

The Federal Environment Agency (UBA) considers it risky to rely on partly unexplored and untested CO2 removal and storage technologies, it said in a recent position paper on carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

“Depending on the site, geological CO2 storage comprises potential risks, for example acidification of ground water or generating local seismic activity. Most CDR methods still require further research and testing before it is possible to apply them,” the UBA wrote.

Technologies aimed at removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere are not yet technically mature enough to contribute to climate action, the German government said in an answer to a parliamentary inquiry at the beginning of the year.

In an evaluation report of the current CO₂ storage legislation from December 2018, the federal government called for an assessment of CCS to reach long term climate targets especially in the industry sector. However, at the time it did not see a necessity to change legislation.

Julian Wettengel

Originally published

by Cleanenergywire.org

May 16, 2019