The development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) suffered a surprise blow last November when the United Kingdom’s widely admired ‘CCS Commercialisation Competition’ was quietly cancelled by the government, just a couple of months before the winning project was to be decided. Already used to store CO2 emissions in underground rock formations at a handful of sites worldwide, the technology offers the potential to decarbonise fossil fuels, but has mostly relied on state grants to get going.

The development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) suffered a surprise blow last November when the United Kingdom’s widely admired ‘CCS Commercialisation Competition’ was quietly cancelled by the government, just a couple of months before the winning project was to be decided. Already used to store CO2 emissions in underground rock formations at a handful of sites worldwide, the technology offers the potential to decarbonise fossil fuels, but has mostly relied on state grants to get going.

The UK scheme was to offer up to £1 billion to one or both of two finalist CCS projects: Shell and SSE’s conversion of an existing gas-fired plant at Peterhead in Scotland, and White Rose – a new coal plant to be built in northern England by a consortium including GE and BOC. Despite this huge setback for the emerging industry, last month provided two interesting new perspectives on both the past and possible future for CCS in the UK and elsewhere. A meeting in London brought the companies behind the two failed bids together to discuss the challenges and successes in taking their projects to the final hurdle, shortly followed by the release of Lord Oxburgh’s report to the government on the future role CCS should play in the country’s plans for decarbonisation.

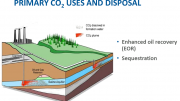

Both the meeting and the report emphasised the fact that the principal challenges facing CCS are not technical, but relate to the considerable regulatory and financial barriers associated with what is a capital intensive and complex process. CO2 must first be separated from the power plant emissions, then transported down a pipeline and injected into offshore wells in the North Sea. Although future carbon capture projects should be able to simply plug into an existing pipeline and reservoir infrastructure, these first projects have the difficult task of developing the entire process chain – requiring huge amounts of investment and carrying considerable risk.

Aside from the small but potentially very costly risk of escaping CO2, issues surround the likely need for several different industry players to operate each stage of the chain, usually involving power companies at the plant side and oil and gas industry companies dealing with the gas itself. This interdependency introduces a ‘cross-chain’ risk associated with the possibility of one member of the chain defaulting on their obligations to the rest, which the White Rose project found particularly difficult to manage and insure against. Shell’s involvement in the Peterhead project managed to circumvent these issues, as the petroleum giant had the will, expertise, and financial means to manage the whole chain alone. However, any future model for a CCS industry is much more likely to follow the White Rose example, in which separate companies will exchange the CO2 in financial transactions.

These sort of unknown risks make debt lenders uncomfortable and ultimately add to the cost of financing such projects. On top of this, another unique expense faced by these ‘first-time’ projects was their obligation to the government to build oversized transport and storage infrastructure which could later be shared by other CO2 emitters in the area, adding £110m to the bill for White Rose. As a consequence, both projects were set to require generous subsidies from the government in the form of the ‘Contracts for Difference’ which are used to guarantee high power prices to low carbon emitters. Although never publicly declared, these would probably have needed to be over £150/MWh, or somewhat higher than contracts offered to new offshore wind farms.

Given the heated recent debate in the UK over subsidising a new nuclear plant (Hinkley Point C) to the tune of a mere £92.50/MWh, these costs may have been what led to the government’s last minute move to axe the competition. However, both projects maintain that any follow on CCS plant, not faced with these initial challenges, could offer a much more competitive rate below £100/MWh. Does there need to be a complete rethink of how this industry is set up in order to skip the costly and politically unpopular first steps? This was the firm conclusion of Lord Oxburgh’s report, which advocates a fairly old idea in the CCS community of setting up a state-owned enterprise with the task of delivering the necessary infrastructure.

This would be split into a power generation entity and a CO2 transport and storage entity, with the government taking on the cross-chain and CO2 storage risks which are initially too difficult for most private sector players to bear. The relatively modest sum of £200-300m was estimated to be sufficient government funding to get such a venture of the ground. At first glance a radical idea for the highly liberalised UK energy market, the report argues that many other large infrastructure projects, such as the London 2012 Olympics and rail links, have received similar government backing, and even large energy projects such as the ever-growing fleet of offshore wind turbines are backed by the majority state-owned enterprises of other nations.

In any case, the ultimate goal would be for the new company to be privatised, in much the same way as happened with the country’s electricity and gas transmission networks. From the beginning, private sector technology providers would play a role in developing each part of the process, but would be free to concentrate on their area of expertise – free from worry about the rest of the business chain. This approach is intended to cement three factors seen as key to guaranteeing the lowest possible price for a first CCS plant: maximising private sector competition, setting out a clear risk and regulatory structure, and maximising economies of scale by building large plants and infrastructure from the start.

The power plants would be pay a separate CO2 company to take their emissions, and be compensated by power price subsidies similar to the existing contracts for difference. A system of tradeable CO2 certificates would be introduced to attest that the greenhouse gas had actually been permanently removed from the atmosphere, whether underground or by conversion to other products. Such is its confidence in this ‘least-cost’ strategy, the report concludes that an energy price figure of around £85/MWh, once projected to be obtainable by projects in 2030, should be immediately possible for a first generation of power plants. Given that this figure was partly intended to take into account the kind of technological improvements that can only be made with experience of large-scale CCS, this estimate may be ambitious, but is not far off the rates thought readily achievable by the two cancelled projects.

Many regard CCS in the power industry as merely a first step towards the real target of decarbonising the equally great CO2 emissions from industrial processes such as cement, steel, and chemical manufacture, for which no other low carbon solutions are available. While the CO2 is often easier to capture, these processes are seen as too challenging for a first wave of projects, as there is currently no financial mechanism to reward industry for imposing such extra costs and damaging the competitiveness of their products on the international market. An ‘industrial capture contract’ is proposed to effectively compensate these emitters, based on short-term contracts with high rewards early on to allow investment to be quickly recouped.

Aiming for the first CCS plants to be rolled out in the early 2020s, the report urges for these steps to be taken as soon as next year, yet it seems doubtful that the current government will be willing to embark on such a venture amidst the uncertainty of ‘Brexit’ and so soon after pushing through the unpopular Hinkley Point nuclear plant. However, following the downbeat post-mortem of the failed CCS competition, Lord Oxburgh’s report brings an optimistic note for an industry which seemed to have been dealt a killer blow in a country once considered to be leading the way. The years of work which went into Peterhead and White Rose should not be considered entirely wasted, as much of their findings have been released into the public domain for future projects to learn from, but human expertise and investor confidence are more rapidly lost. For CCS to be resurrected from the ashes of this latest failure and faith in long-term policy restored, it is abundantly clear that government will need to take on a much more prominent role.

Toby Lockwood

Be the first to comment on "Is there a way back for CCS in the UK?"