If you’ve ever rented or bought a house, you’ve probably come across energy performance certificates (EPCs). These certificates, with their brightly coloured bar charts, adorn estate agents’ windows and tell prospective tenants and buyers how energy efficient their property is on a scale of A to G, with A being most efficient and G, least.

To produce these certificates for an existing home, an energy assessor visits and take measurements, noting the building’s construction and energy systems. They enter this data into software called the reduced standard assessment procedure (RdSAP), which generates the energy-efficiency rating based on some standard assumptions. EPCs can also recommend changes, known as retrofits, that would improve the home’s energy performance, such as adding insulation to the loft or buying a more efficient boiler.

It may sound dull, but home energy use accounts for nearly a fifth of the UK’s total emissions. The UK has some of the oldest building stock in Europe, with 36% of UK homes built before 1945 and at least 75% predicted to still be in use by 2050. Just focusing on making new homes energy efficient isn’t enough – most of the work will involve retrofitting existing houses to reduce their energy demand.

Most rented properties in the UK must have an EPC rating of at least E if they are to be let. The Committee on Climate Change, which advises the UK government on its legally binding climate targets, recently recommended that all homes for rent or sale should have to achieve a C rating by 2028, and that all homes should be aiming for this by 2035.

It all sounds quite sensible. We know that retrofitting is necessary on a massive scale, we have a tool that people are relatively familiar with and which appears to measure the thing that we need to improve. But all this only works if EPCs provide a reasonably accurate picture of the energy performance of each house.

Unfortunately, that isn’t the case.

EPC ratings versus actual energy use

Research from across Europe suggests EPCs are often inaccurate when predicting energy use. They tend to overestimate energy use for older buildings and underestimate it for newer buildings.

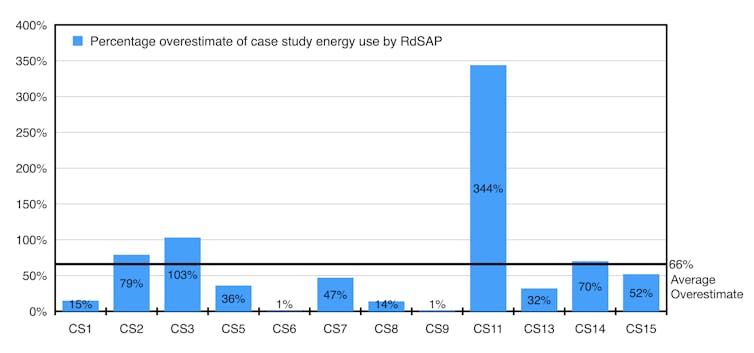

My own research on buildings built before 1945 in north-west England supports this. Across 12 buildings, the average overestimation by the RdSAP software was 66%, meaning that the houses were actually using much less energy than the model predicted.

There are several reasons for this inaccuracy. First, RdSAP has been shown to poorly represent how well traditional materials like solid stone walls retain heat. Second, it doesn’t take into account items that older buildings may already have that enhance energy efficiency, such as traditional internal shutters, which can reduce heat loss significantly.

It also assumes that people heat all of their building to standard schedules. My own and other research has shown that this is rarely the case, with many people only heating certain parts of their houses and often heating them to lower temperatures or for less time than the model assumes.

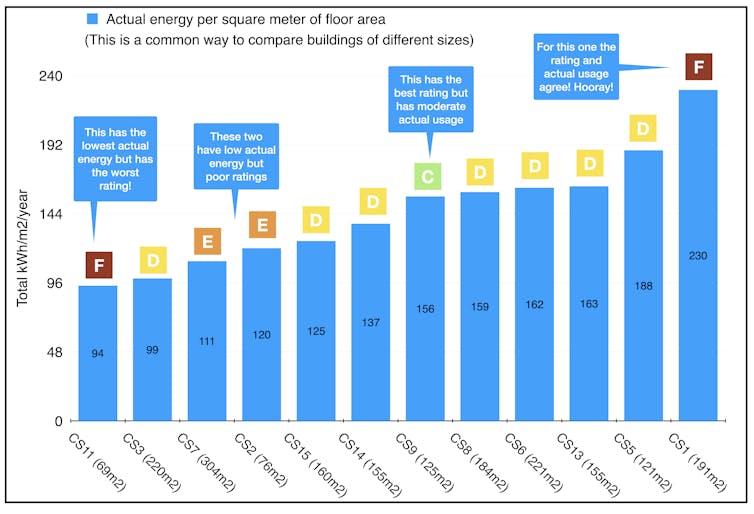

If a house is predicted to use more energy than it really does, retrofitting will not cut energy use and carbon emissions as predicted. After all, you can’t save energy that you’re not using in the first place. This is important, as retrofits are often supposed to be paid for by predicted savings on energy bills. Resources for retrofitting must be targeted where they will make the most difference, on the worst-performing buildings. But my research shows that focusing on buildings with the lowest EPC ratings may not address those that are the least energy efficient in reality.

EPC retrofit recommendations can be inappropriate for older buildings too, which often behave differently to modern buildings. Adding insulation to solid stone walls, unless very carefully executed, can trap moisture inside. Older buildings contribute to the character of villages, towns and cities. Some changes, like replacing original windows with double glazing, can be inappropriate, but EPCs lack the flexibility to recommend more sensitive alterations, like traditional shutters.

EPCs aren’t working, but especially for the 36% of pre-1945 UK homes. These certificates must better represent traditional construction, more accurately capture home-energy behaviour and provide retrofit recommendations that match the circumstances of each building.

Everyone agrees on the need to reduce the amount of energy used and carbon emitted from our homes. But how we measure these things must improve significantly if we are to tackle the climate emergency.![]()

Freya Wise, PhD Candidate in Sustainability and the Built Environment, The Open University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.