The world added more non-fossil power last year than ever before, but energy demand rose by even more.

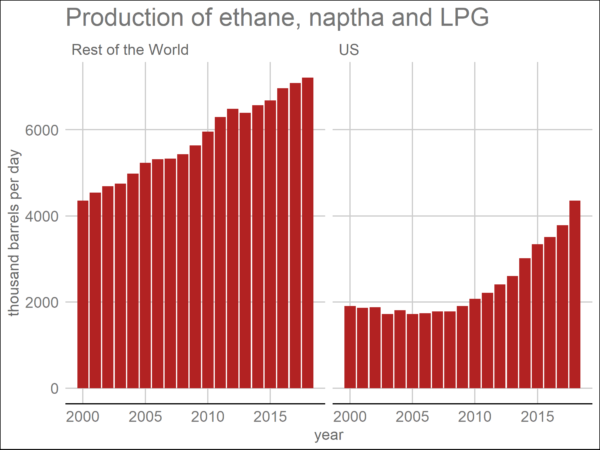

Last year’s rise in global CO2 emissions – the largest since 2011 – was driven in part by a surge in demand for petrochemicals used largely to manufacture plastic materials, according to statistics in BP’s latest world energy review.

Growth in production of naptha, ethane and LPG – which primarily function as petrochemical feedstocks – accounted for half of oil demand growth in 2018, far more than in previous years.

Emissions were also pushed up by a rebound in China’s coal use – tied to the steel industry – and a jump in demand for heating and cooling around the world, largely due to yearly variation, but potentially a sign of things to come as climate change proceeds.

The petrochemical boom comes as the oil industry is pinning its hopes on the petrochemical industry as electric vehicles weaken growth in demand for petrol, and weak manufacturing growth and the US-China trade war cut into diesel demand.

Petrochemicals account for 12% of the world’s oil use and the sector is expected to drive one third of oil demand growth to 2030, which means it would grow 3x as fast as other oil demand.

It follows a BP projection that saw growth in the sector’s use of liquid fuels fall by more than 80% and total demand growth more than cut in half in the event of a single-use plastics ban.

Surging demand outstrips clean energy growth

In 2018, more non-fossil electricity production was added to grids worldwide than ever before. And yet global CO2 emissions from the energy sector increased by the largest amount since 2011, according to BP’s annual Statistical Review on World’s Energy.

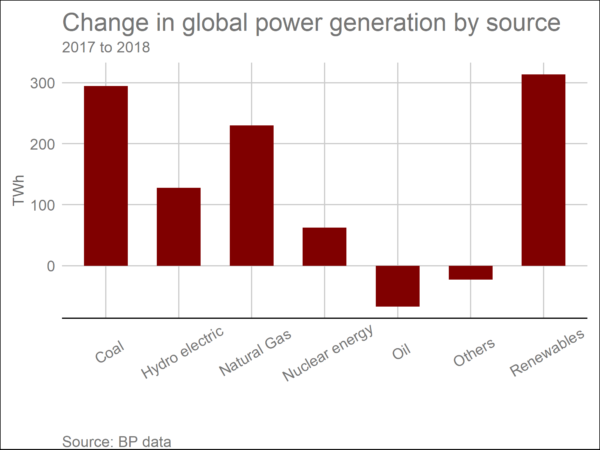

The amount of power generated from renewables, hydropower and nuclear increased by 500 terawatt-hours in 2018, two times the annual consumption of California in one year, and a dramatic gain over the previous record of 400 terawatt-hours, from 2017.

But the real story last year was that of a catastrophic rise in energy demand.

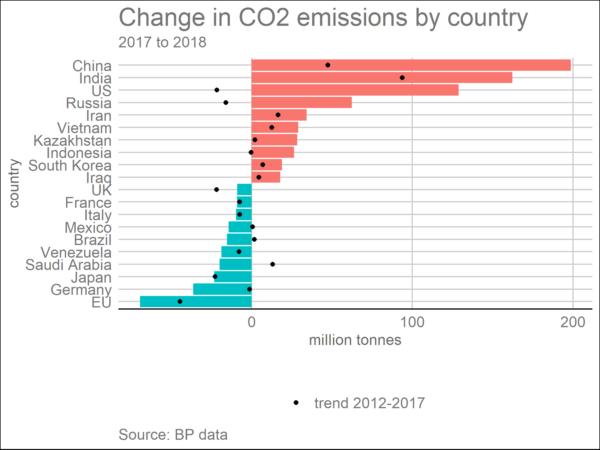

Energy sector CO2 emissions increased fastest since 2011

China, India and the U.S. were responsible for by far the largest increases in emissions, with all of them seeing much faster growth than the trend over the previous five years. Germany and Japan contributed the largest reductions in emissions.

The reasons for faster demand growth include a rapid increase in plastics production, the roaring return of so-called smokestack industries in China, and exceptionally hot and cold temperature extremes which increased the need for heating and air conditioning. Many of these demand drivers, however, are likely to unwind in 2019.

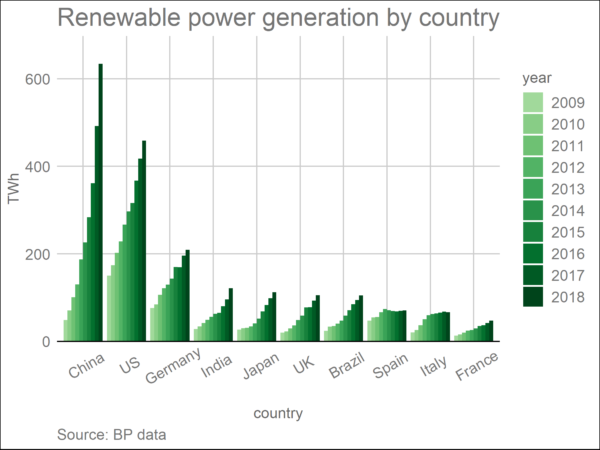

Renewable energy breakthroughs in India and UK

The rise in energy demand over-shadowed dramatic increases in installations of non-fossil fuel energy.

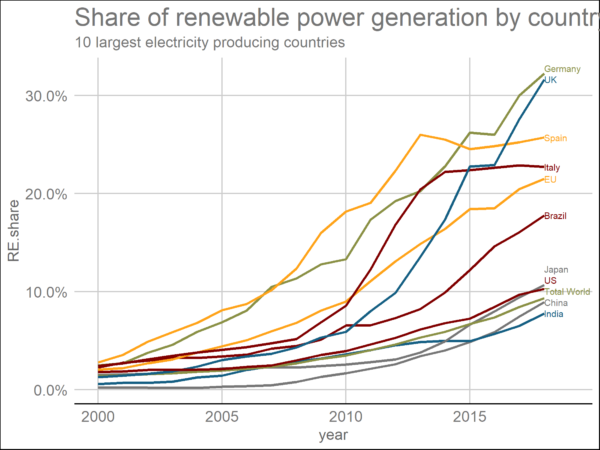

India has recently overtaken the UK and Japan in the total amount of power it is generating from renewables, becoming the fourth largest producer in the world.

And while new investments slowed in China, improved operating rates kept generation growing at near-record rate.

The UK, meanwhile, continued its impressive progress, having gone from just over 5% renewable power generation in 2010 to over 30% in 2018, and coming within a hair of overtaking Germany.

But as demand growth accelerated, even these impressive gains in renewable energy only delivered one-third of the overall increase in power generation, with hydro and nuclear bringing the non-fossil total to a half. The other half was covered by coal and gas, pushing emissions up.

Annual renewable power additions will need to triple in order for renewables to start pushing fossil fuels out of the power sector. At current growth rates this is achievable, but difficult.

Outlook: Emissions growth slowing in 2019

The surge in global CO2 emissions seen in 2017-18 shows signs of leveling off in 2019.

Power demand growth in China slowed to 4% in the first four months of 2019 against 8% the same period of the previous year. China’s diesel demand is also falling rapidly, after rising in 2018.

Global oil demand growth is easing. U.S. CO2 emissions have fallen for three consecutive months.

Carbon prices in the EU have finally recovered and are expected to push coal use and CO2 emissions down.

June, 14 2019

This article is originally published by Unearthed