Last April the town of Laporte, Texas, was the setting for what could prove to be a turning point in the losing battle against carbon emissions. In this otherwise nondescript Houston suburb, tech start-up Net Power successfully fired up a much-anticipated test facility for a new type of gas-fired power plant which promises to capture its CO2 emissions at no extra cost.

Last April the town of Laporte, Texas, was the setting for what could prove to be a turning point in the losing battle against carbon emissions. In this otherwise nondescript Houston suburb, tech start-up Net Power successfully fired up a much-anticipated test facility for a new type of gas-fired power plant which promises to capture its CO2 emissions at no extra cost.

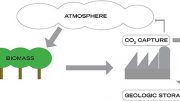

Despite forecasts from international bodies such as the International Energy Agency and IPCC repeatedly highlighting the need for widespread use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology, which can purify and store CO2 emissions deep underground, existing technologies come at a cost which few governments are prepared to subsidise. Only two power plants worldwide (both coal-fired) have fitted CCS to date, and there are currently no concrete plans for more. If NET Power’s facility manages to deliver on its remarkable claims, this could quickly change.

The plant is based on an entirely new power generation concept known as the Allam Cycle, after its inventor, British chemical engineer Rodney Allam. Ordinary gas power plants work in the same way as aeroplane jet engines – natural gas is burnt in compressed air, and the hot exhaust is used to drive a turbine. The most efficient plants then use any heat left in the air to turn water into steam which powers an additional steam turbine. In the place of air or water to drive its turbine, the Allam Cycle uses CO2 at temperatures and pressures at which it behaves neither as a gas nor a liquid. This form of CO2, known as ‘supercritical’, has long been recognised as ideally suited to the task of turning heat energy into electricity. It remains much denser than steam or air while releasing its energy, so can be used in many times smaller turbines, while its thermal properties allow it to run at high efficiencies.

In the Allam Cycle, natural gas is burnt in a high-pressure mixture of pure oxygen and CO2 – in itself a challenge as CO2 is usually used to put out fires. The combustion produces heat, steam, and more CO2 which drive the compact turbine before the gases are cooled to condense out the steam as water and leave a pure stream of CO2. The majority of this CO2 is pressurised and returned to the combustion chamber to flow through the turbine again, but some must be removed to balance the extra CO2 from the burning gas. Ideally, this would then be injected deep underground into the porous rock where it can remain for millions of years like the natural gas from which it came. A subtle, but unique feature of the Allam Cycle is that the hot exhaust gases are used to heat up the cooled gases returning to the turbine, and some extra heat is needed to make this work. Conveniently, this heat can be taken from the air separation machines required to produce the pure oxygen, neatly tying the design together.

Professor Allam came up with his eponymous power cycle following a meeting with Bill Brown – a disillusioned Wall Street banker in search of a technology which could change the world. Along with fellow MIT graduate Miles Palmer, Bill Brown is the co-founder of 8 Rivers Capital, a North Carolina-based company which co-owns the NET Power venture together with energy company Exelon and construction firm CB&I.

The entrepreneurs quickly formed a vital relationship with Japanese technology firm Toshiba, who have designed and built the new combustor and turbine needed for the technology. In early 2016, construction began at the LaPorte facility, which is big enough to produce 25 MW of electricity – about ten times smaller than a full-size power plant.

However, the turbine is already full-sized and only being run at a fraction of its capacity, while Toshiba is working on a larger combustor, so scaling up the facility could be relatively quick and easy. 8 Rivers are already designing a 300 MW version of the plant, which – if all goes to plan at the test site – they ambitiously hope to start building in 2021.

Although the US recently passed a rule which will provide a significant tax credit to companies capturing CO2, the business case for CCS for the sake of the climate alone is still limited. Fortunately, the US also has a thriving market for using CO2 to push more oil out of depleted oil wells. NET Power calculates that, while its first few plants will cost slightly more than a conventional gas plant (without CO2 capture), a combination of sales of CO2 to oil companies and sales of pure nitrogen and argon gases from its air separation plants will still make them competitive without needing any climate-based incentives. Once several plants have been built, the design and supply chain will have been optimised enough to reduce its costs to below that of a conventional gas power plant, but with the crucial bonus of pure CO2. 8 Rivers is highly cautious of relying on climate policy to make its business work and has envisioned other potential markets for CO2, such as using it to remove the unwanted sulphur compounds found in many natural gas reservoirs. While the company is partly banking on forecasts that demand for new, clean fossil power plants will grow worldwide – driven by the coming electrification of transport and heat – it has recently put forward a solution for cleaning up existing power plants as well.

This idea would use a form of the Allam Cycle to turn natural gas to hydrogen, which can then be used as a clean fuel in many existing gas turbines. Natural gas may be a rising star in power generation, but coal, its dirtier fossil cousin, remains the largest source of power worldwide. 8 Rivers have not ignored this business opportunity either, having worked for several years to develop a form of the process which can run on ‘gasified’ coal, again at a lower cost than a conventional coal plant.

Carbon capture and storage faces other challenges, not least the likely need for government involvement in helping explore possible CO2 storage sites, develop infrastructure, and underwrite some of the risks involved. If these political barriers could be overcome, existing CO2 capture technologies would perhaps already be making an impact.

However, quite apart from its attractive economics, the Allam Cycle may possess an essential psychological asset in that no extra fossil fuel is consumed in separating out its CO2 emissions. The current model of extracting and burning more fossil fuel to clean up fossil fuels finds few instant fans among the public or policymakers. If the next few months of testing prove that Allam Cycle really lives up to its hype, the stage is set for winning hearts and minds over to a CCS revolution.

Toby Lockwood