Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1565

Dagomar Degroot, Georgetown University

In recent weeks, catastrophic floods overwhelmed towns in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, inundated subway tunnels in China, swept through northwestern Africa and triggered deadly landslides in India and Japan. Heat and drought fanned wildfires in the North American West and Siberia, contributed to water shortages in Iran, and worsened famines in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya.

Extremes like these are increasingly caused or worsened by human activities heating up Earth’s climate. For thousands of years, Earth’s climate has not changed anywhere near as quickly or profoundly as it’s changing today.

Yet on a smaller scale, humans have seen waves of extreme weather events coincide with temperature changes before. It happened during what’s known as the Little Ice Age, a period between the 14th and 19th centuries that was marked by large volcanic eruptions and bitter cold spells in parts of the world.

The global average temperature is believed to have cooled by less than a half-degree Celsius (less than 0.9 F) during even the chilliest decades of the Little Ice Age, but locally, extremes were common.

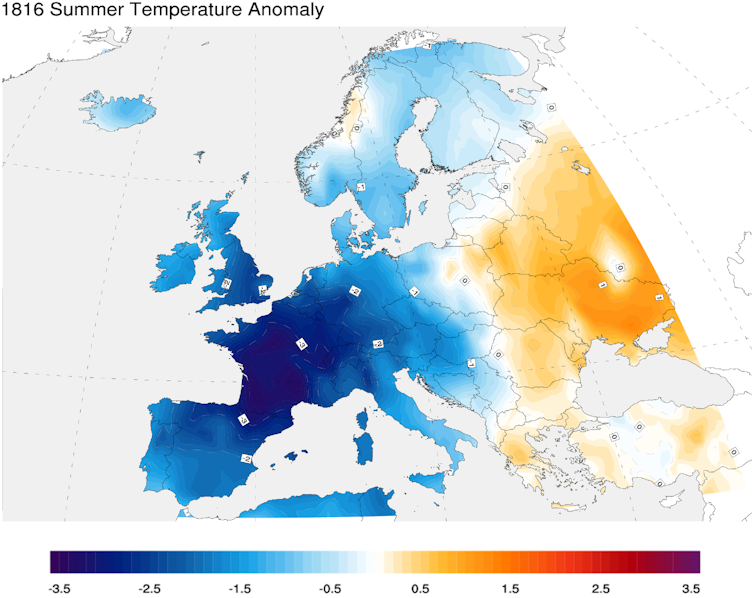

In diaries and letters from that period, people wrote about “years without a summer,” when wintry weather persisted long after spring. In one such summer, in 1816, cold that followed a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia ruined crops across parts of Europe and North America. Less well known are the unusually cold European summers of 1587, 1628 and 1675, when unseasonal frost provoked fear and, in some places, hunger.

“It is horribly cold,” author Marie de Rabutin-Chantal wrote from Paris during the last of these years; “the behavior of the sun and of the seasons has changed.”

Winters could be equally terrifying. People reported 17th-century blizzards as far south as Florida and the Chinese province of Fujian. Sea ice trapped ships, repeatedly enclosed the Chesapeake Bay and froze over rivers from the Bosporus to the Meuse. In early 1658, ice so completely covered the Baltic Sea that a Swedish army marched across the water separating Sweden and Denmark to besiege Copenhagen. Poems and songs suggest people simply froze to death while huddling in their homes.

These were cold snaps, not heat waves, but the overall story should seem familiar: A small global change in climate dramatically altered the likelihood of extreme local weather. Scholars who study the history of climate and society, like me, identify these changes in the past and find out how human populations responded.

What’s behind the extremes

We know about the Little Ice Age because the natural world is full of things like trees, stalagmites and ice sheets that respond to weather while growing or accumulating gradually over time. Specialists can use past fluctuations in their growth or chemistry as indicators of fluctuations in climate and thereby create graphs or maps – reconstructions – that show historical climate changes.

These reconstructions reveal that waves of cooling swept across much of the world. They also suggest likely causes – including a series of explosive volcanic eruptions that abruptly released sunlight-scattering dust into the stratosphere; and slow, internal variability in regional patterns of atmospheric and oceanic circulation.

These causes could only cool the Earth by a few tenths of a degree Celsius during the chilliest waves of the Little Ice Age, however. And the cooling was not nearly as consistent as present-day warming.

Small global trends can mask far bigger local changes. Studies have suggested that modest cooling created by volcanic eruptions can reduce the usual contrast between temperatures over land and sea, because land heats and cools faster than oceans. Since that contrast powers the monsoons, the African and East Asian summer monsoons can weaken after big eruptions. That likely disturbed atmospheric circulation all the way into the North Atlantic, reducing the flow of warm air into Europe. This is why parts of Western Europe, for example, may have cooled by more than 3 C (5.4 F) even as the rest of the world cooled far less during the 1816 year without a summer.

Dagomar Degroot, CC BY-ND

Feedback loops also amplified and sustained regional cooling, similar to how they amplify regional warming today. In the Arctic, for example, cooler temperatures can mean more, longer-lasting sea ice. Ice reflects more sunlight back into space than water does, and that feedback loop leads to more cooling, more ice and so on. As a result, the comparatively modest climate changes of the Little Ice Age likely had profound local impacts.

Changing patterns of atmospheric circulation and pressure also led in many regions to remarkably wet, dry or stormy weather.

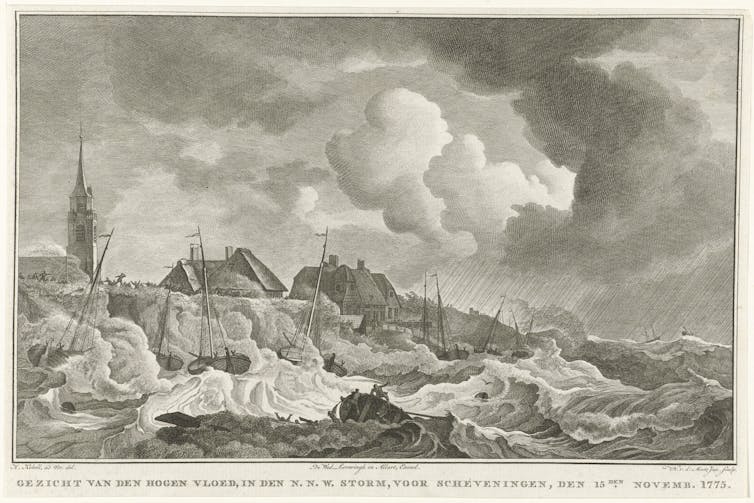

Heavy sea ice in the Greenland Sea may have diverted the North Atlantic storm track south, funneling severe gales toward the dikes and dams of what are today the Netherlands and Belgium. Thousands of people succumbed in the 1570 All Saints’ Day Flood along the German and Dutch coast, and again in the Christmas Flood of 1717. Heavy precipitation and water pooling behind dams of melting ice repeatedly overwhelmed inadequate flood defenses and inundated central and Western Europe. “Who would not take pity on the city?” one chronicler lamented after seeing his town under water and then on fire in 1602. “One storm, one flood, one fire destroyed it all.”

Noach van der Meer II, after Hendrik Kobell

Cooling sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic Ocean probably also diverted the rain-giving winds around the equator to the south, provoking droughts that undermined the water infrastructure of 15th-century Angkor.

Owing perhaps to the modest cooling of volcanic dust veils, disrupted patterns of atmospheric circulation led in the 16th century to severe droughts that contributed to food shortages across the Ottoman Empire. In 1640, the grand canal that supplied Beijing with food simply dried up, and a short but profound drought in 1666 primed the wooden infrastructure of European cities for a wave of catastrophic urban fires.

How does it apply to today?

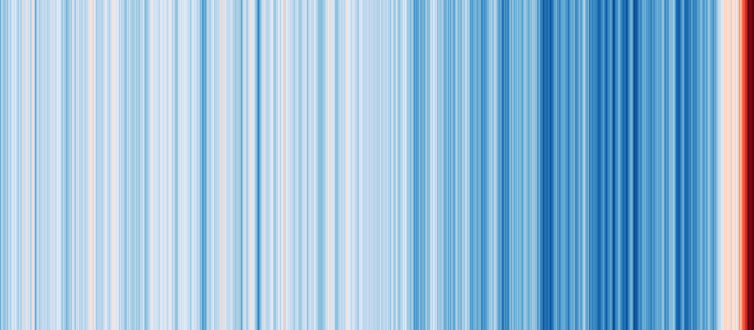

Today, the temperature shift is going in the other direction – with global temperatures already 1 C (1.8 F) higher than before the industrial era, and local, sometimes devastating, extremes occurring around the world.

New research has found that extreme heat waves, those that don’t just break records but shatter them, become more common when temperatures change rapidly.

These serve as a warning to governments to redouble their efforts to limit warming to 1.5 C (2.7 F), relative to the 20th-century average, while also investing in the development and deployment of technologies that filter greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere.

Ed Hawkins

Restoring the chemistry of the atmosphere will still take many decades after countries bring down their greenhouse gas emissions, and so communities must adapt to a hotter and less habitable planet. Nations and

communities might learn from some of the success stories of the Little Ice Age: Populations that prospered were often those that provided for their poor, established diverse trade networks, migrated from vulnerable environments, and above all adapted proactively to new environmental realities.

People who lived through the Little Ice Age lacked perhaps the most important resource available today: the ability to learn from the long global history of human responses to climate change.

[Get our best science and technology stories. Sign up for The Conversation’s science newsletter.]![]()

Dagomar Degroot, Associate Professor of Environmental History, Georgetown University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.