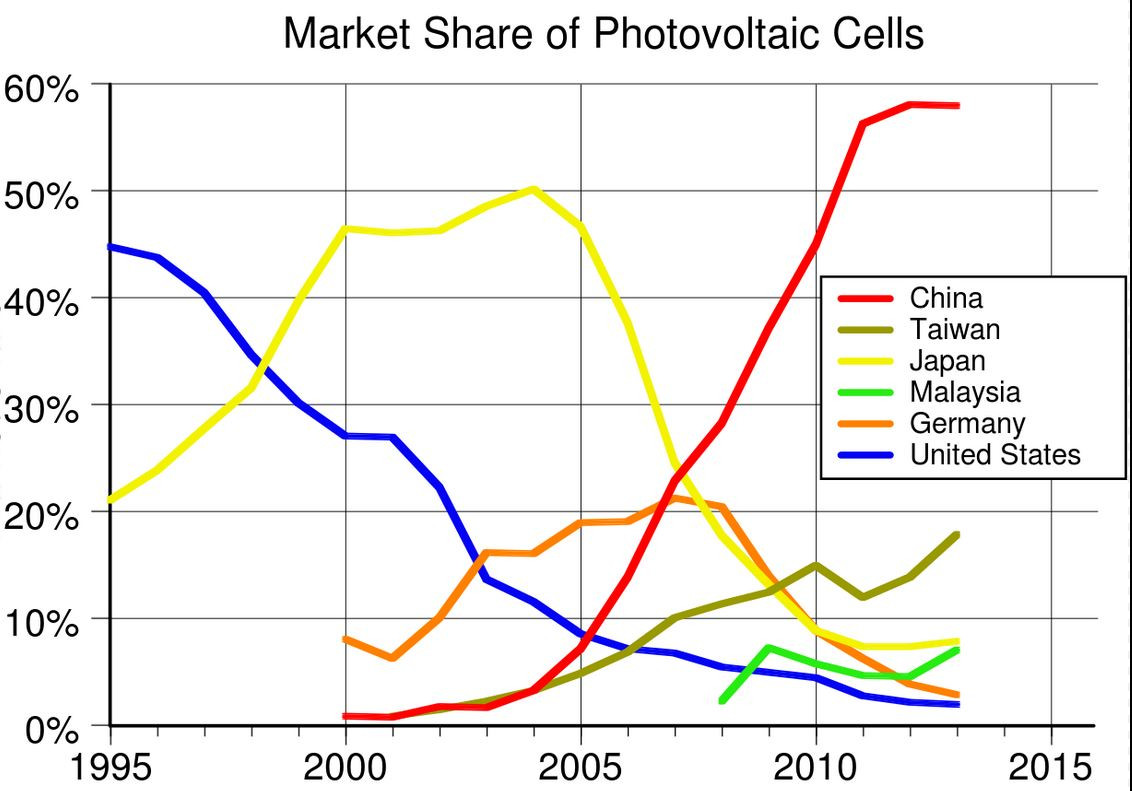

The rivalry between Europe and China in emission-free hydrogen technologies could become one of the defining business stories in the global effort to stop climate change. Scarred by its painful experience in solar PV manufacturing, which was developed in Europe at high cost only to later move to China, Europe is not taking any chances with hydrogen. In a bid to outcompete China and fulfil its ambition to become climate-neutral, Europe has launched a massive green hydrogen push to decarbonise industry and aviation and secure promising export opportunities. Green hydrogen is viewed by many as key to reaching “net-zero” emission targets, but a global rollout of the technology won’t be possible without steep price decreases. This could make competition between the EU and China crucial to global decarbonisation efforts.

Green hydrogen made with water and renewable power has emerged as a “silver bullet” technology to clean up many CO2-intensive sectors where emission reductions are particularly hard, such as heavy industry and aviation. To date, its high costs stand in the way of a global deployment in the fight against climate change. But there is hope: the commercial rivalry between Europe and China, which could force prices down rapidly.

“Competition in hydrogen technology between Europe and China will be crucial to kickstart a global hydrogen economy because it will drive down the cost of the technology, which will play a key role in cutting emissions in many sectors,” Kobad Bhavnagri, head of industrial decarbonisation at research service BloombergNEF, told Clean Energy Wire.

“In turn, this will enable more countries to commit to net-zero targets. We’ve seen this development in solar PV, where competition in manufacturing between Europe and China led to a drastic drop in prices, changing the economics, and thus paving the way for today’s global roll-out of this technology and renewable targets in many countries,” Bhavnagri said [Read the full interview here]. “It will be exciting to watch how this competition will unfold in the years to come.”

Green hydrogen remains more expensive than the conventional variety made from fossil fuels because the equipment to make it is costly, and because the process requires enormous amounts of power. As a result, private companies currently have no incentives to produce it in large amounts.

Harnessing the “rock star of new energies”

“With the state of technology in Europe, the economics and the policy instruments at hand, the European Union can take the lead globally,” European Commission Vice President Frans Timmermans, who is also the EU’s climate commissioner, said during the presentation of the bloc’s hydrogen strategy in early July. He added that green hydrogen had become the “rockstar of new energies all across the world, and especially in Europe”.

European policymakers and industry regularly single out China as the most important competitor in the EU’s ambition. “We are still leading as Europeans. But especially China is challenging that position,” Jorgo Chatzimarkakis of the Hydrogen Europe business association told Euractiv in the spring. “The competition is catching up and we believe they are only 2-3 years behind us,” Chatzimarkakis told Clean Energy Wire. German economy minister Peter Altmaier also said that his country must beat Asian countries to claim global leadership in the technology, naming China as an example. “Our goal is clear. We want Germany to be the global No. 1 in hydrogen technology,” Altmaier said.

Green hydrogen is made in electrolysers that split water into its basic components, oxygen and hydrogen, using renewable electricity. Because burning hydrogen only releases water, it has the potential to power some of today’s most polluting economic activities without causing any emissions. But due to the high costs of electrolysis, 95 percent of commercially available hydrogen is currently produced on the basis of fossil fuels, in a process called steam methane reformation, according to the bank JP Morgan. But making this “grey” hydrogen generates large amounts of climate-damaging CO2 emissions. This production method can be cleaned up using carbon capture and storage to make “blue” hydrogen, but it does not become emission-free. Only “green” hydrogen made with renewables is considered completely sustainable.

This is why the costs of making renewable hydrogen will have to come down fast to enable the deep emission cuts needed for net-zero climate targets in industries across the world. “Once the industry scales up, renewable hydrogen could be produced from wind or solar power for the same price as natural gas in most of Europe and Asia,” BNEF reports. “These production costs would make green gas affordable and puts the prospects for a truly clean economy in sight.”

Business information service IHS Markit forecasts that carbon-free green hydrogen could be cost competitive by 2030. “Costs for producing green hydrogen have fallen 50 percent since 2015 and could be reduced by an additional 30 percent by 2025 due to the benefits of increased scale and more standardised manufacturing, among other factors,” IHS Markit said, adding the overall share in the energy mix will depend on the desired extent of decarbonisation. “The greater the degree of a decarbonisation, the greater the likely role of hydrogen in the energy future.”

From an economic perspective, the prospect of a rapidly expanding global hydrogen economy promises rich rewards for countries with a technological and competitive edge. The EU has set its sights on taking a large slice of the pie.

“Clean hydrogen is key for a strong, competitive and carbon-free European economy,” Timmermans said. “We are leading the world in this technology and we want to stay ahead. But we need to make an extra effort to stay ahead because the rest of the world is quickly catching up.”

Hydrogen promises to be an extremely versatile tool – it can be used to store energy for an unlimited time, and as an energy source for many sectors. It can also be used to make synthetic fuels that can replace fossil fuels as a feedstock, for example to make plastics. A further advantage is that it can be traded internationally, potentially turning into a globally traded commodity.

The EU wants to take advantage of this trend by bolstering the hydrogen sector, which could support up to 1 million jobs in the region by the middle of the century. It expects cumulative investments to reach between 180 and 470 billion euros in the bloc alone. “Over the coming years, cleantech will be a global growth engine,” Timmermans said.

Within the EU, Germany has been a particularly outspoken advocate of green hydrogen. The country boasts strong electrolyser manufacturers such as Siemens, thyssenkrupp, Sunfire and others. If Germany can hold onto its current share of electrolyser production in global markets, which stands at around 20 percent (see graph), the industry could create up to 470,000 jobs – equivalent to about half of all jobs currently in the country’s iconic car industry, according to the German Economic Institute (IW). Additional jobs created in companies making renewable energy, which will be required to run hydrogen production, will come on top.

The EU Commission’s hydrogen strategy contains a three-step plan, which starts with the construction of electrolysers to produce green hydrogen for use in industries (steel, chemicals, refineries) by 2024, followed by the creation of local hydrogen production hotspots, which will be linked to industrial users in so-called “hydrogen valleys”, by 2030. With increasing demand, these hotspots will be joined to create the backbone of a large European hydrogen infrastructure.

The EU wants to see at least 6 gigawatts (GW) of renewable electrolyser capacity that can produce up to 1 million tonnes of renewable hydrogen realised by 2024. This is equivalent to using the entire output of six large power stations only to make hydrogen. By 2030, the EU aims to produce 10 million tonnes with a combined electrolyser capacity of 40 GW. In its own national strategy, Germany aims for 5 GW by 2030.

“The approach the European strategy is taking is very much one of trying to ensure a future for European manufacturers. It seems to be a defence mechanism against competition from China and other low-cost manufacturers,” he added.

Companies in Europe have jumped at the opportunity to become suppliers for the hydrogen economy. Coinciding with the announcement of Germany’s strategy, steelmaker thyssenkrupp said it planned to expand its production capacities for water electrolysis to make green hydrogen at the gigawatt scale. “Many countries around the world are currently planning to enter the hydrogen economy. Water electrolysis is increasingly emerging as a key technology for building a sustainable, flexible energy system and carbon-free industry. This opens up new markets for us,” said Sami Pelkonen, CEO of thyssenkrupp’s Chemical & Process Technologies business unit. The company also formed a partnership with utility E.ON to build a hydrogen infrastructure.

British electrolyser maker ITM Power also said it plans to massively expand its production in cooperation with Danish power company Ørsted. “What is needed now is to scale up the electrolyser technology and bring the cost down,” said Anders Christian Nordstrøm, Ørsted’s vice president for hydrogen.

Chinese manufacturers are ahead of Europe in the low-cost manufacturing of hydrogen production equipment – their electrolysers currently cost only a fraction of European ones. “Because the Chinese market is so large, their producers benefit from economies of scale, automation, etc. to a much larger extent than EU or US ones,” said Hydrogen Europe’s Chatzimarkakis, adding that scale “has a huge impact on all costs along the whole value chain.” But several industry experts said there are doubts about the quality and reliability of Chinese electrolysers.

“We see China as an important green hydrogen competitor because the country established it early on as a core element of its climate plan,” a source at a prominent European electrolyser manufacturer told Clean Energy Wire. “European manufacturers clearly lead the way when it comes to efficiency, scalability and flexibility, while Chinese competitors use simpler technologies, but enjoy cost advantages.”

At present, Chinese electrolyser manufacturers have barely begun to compete with European companies because they mostly sell domestically and to markets other than Western Europe, Australia and the U.S, according to BNEF. Moreover, the country currently is a major importer of European hydrogen technology, according to Chatzimarkakis. “Provided we keep the lead [in many hydrogen technologies], China can be a huge potential market to export equipment and technology to,” he added.

German economy minister Altmaier has put China’s cost advantage down to cheaper labour, adding that “the ship has by no means sailed” for domestic firms. Most experts agree that European companies can still catch up on prices. BNEF forecasts that Western companies can converge to the Chinese cost level by 2030 through “a combination of increased scale, automation and moving production to countries with cheaper workers” (see graph). But BNEF’s Bhavnagri also warned: “I wouldn’t say at all that it is a foregone conclusion that the European products can be manufactured for the same price as the Chinese, but the forces of competition and economics suggest that either they will need to, or they’ll get outcompeted.”

Industry experts said Europe, and Germany in particular, are determined to prevent their fledgling hydrogen industry from following the example of the continent’s solar industry.

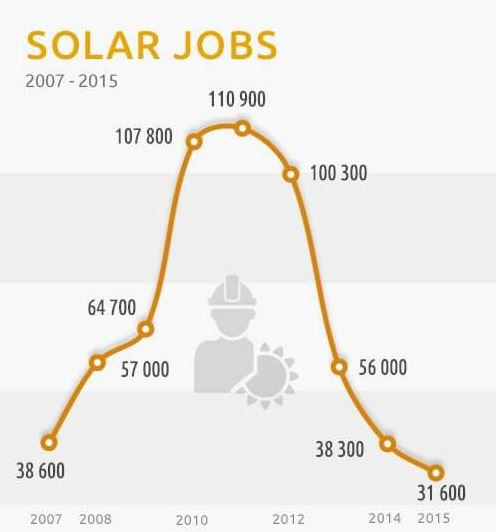

At the start of the millennium, Germany was the world’s largest market for solar panels and a technology pioneer. Its solar industry experienced a spectacular boom in the mid-2000s after the introduction of generous support payments. But when these were slashed and cheaper Chinese solar PV modules entered the market, the German industry collapsed, resulting in tens of thousands of job losses, and felling major players such as Q-Cells, Solon, Conergy and SolarWorld.

“With its hydrogen strategy, Germany is not only trying to fulfil its emission reduction obligations, but it is also actively trying to become a leader. It is approaching this through lessons learned from the solar fiasco,” said Gniewomir.

The EU and China are fierce commercial rivals in many technological areas, but their economies also fundamentally depend on each other. China is the EU’s second-biggest trading partner behind the United States, and the EU is China’s biggest trading partner. The two blocs trade on average over one billion euros per day and are currently in the process of completing a comprehensive agreement on investments. The European Commission says the aim of the deal is to improve European companies’ access to the Chinese market.

But trade relations are not always smooth, especially in the sensitive energy sector. The EU tried to reign in the flood of Chinese solar modules with tariffs, and the German government bought a temporary stake in power transmission grid operator 50Hertz “on national security grounds” to fend off a Chinese involvement in what it considered critical infrastructure in 2018.

Boom and bust – Solar jobs in Germany. Source Wikipedia

The green hydrogen contest with Europe will be shaped decisively by Chinese government decisions. The country started early to promote hydrogen technologies with policies on a national, provincial and municipal level. But given that China has not committed yet to becoming climate-neutral, in contrast to Europe, it has put much less emphasis on green hydrogen.

The country does not yet have a dedicated green hydrogen strategy or detailed targets, but local industry has forecast a growing role for the emission-free gas. For example, a white paper by the China Hydrogen Alliance, composed of companies, universities and research institutes, predicted in 2019 that the majority of hydrogen production would shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy by mid-century, says Run Zhang-Class, who worked for a Chinese energy group and is now China project manager at energy transition think tank Agora Energiewende.*

“The critical value of hydrogen technology application is to guarantee energy security, which is the priority of China’s energy development, given China’s high dependency on imported oil and gas,” Zhang said. The National Development and Reform Commission’s (NDRC) guidelines for industrial restructuring also encouraged high-efficiency hydrogen production, transportation and storage development, she added.

China is the world’s largest hydrogen producer. It makes 22 million tons per year, equivalent to one-third of the world’s total. But most of China’s hydrogen comes from coal – it has nearly 1,000 coal gasifiers in operation, accounting for 5 percent of China’s total coal consumption, according to a report by Cleantech Group, a US company supporting and advising on the roll-out of renewables.

One focus of Chinas hydrogen policy has been the promotion of fuel cells, which convert hydrogen back into electricity to power cars, buses and heating, for example. Here, China is considered a pioneer and has dedicated targets – it’s aiming for 5,000 fuel-cell vehicles by 2020 and 1 million by 2030. “China has been pushing especially strong for hydrogen in mobility applications,” said Hydrogen Europe’s Chatzimarkakis. “China might lead the world in battery vehicles, but until recently it was a relative laggard in hydrogen, but now, it’s catching up,” according to S&P Global Platts, an energy and commodities information service.

But again, there is no particular focus on using green hydrogen to power its fuel cells yet – at present, only 3 percent of China’s hydrogen is made from renewable resources, according to S&P Global Platts. “Breakthroughs in production, transport and storage as well as fuel cell technology will be needed for China to not only catch up, but become a leader in the global hydrogen economy.”

Hydrogen made with coal is very cheap compared to green hydrogen in China. “Production costs for hydrogen remains three times less than hydrogen production via water electrolysis,” Cleantech Group noted in a report. “Given this cost gap, the lingering question for China will be whether electrolyser cost projects can decrease enough to warrant a global transition from coal-based hydrogen production to electrolysis hydrogen production.”

A commitment to become climate neutral by mid-century would sharply change the equations in China’s hydrogen plans and likely force it to fully embrace the green variety. But it remains totally uncertain whether this might be on the cards.

Last summer, Chinese Science and Technology Minister Wan Gang called for China to “look into establishing a hydrogen society,” according to the Cleantech Group. “Given the minister made a similar call two decades ago on vehicle electrification, which played a role in China’s current market dominance, close attention is being paid,” the report said.

Climate activists and many Western think tanks and consultancies have urged China to join the EU’s strive for zero emissions – not only to fight climate change but also to profit economically. The Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI), a US non-profit advising on the energy transition, argued that China can become carbon-neutral by mid-century without denting economic growth. On the contrary, the institute argued that “China is well placed to gain technological competitive advantage from the transition to net zero emissions” and urged the country to support hydrogen electrolysis. Business consultancy McKinsey also said China could tap new sources of economic growth by making a rapid and orderly transition to a low-emissions pathway, adding that China needed to change its power and fuel mix by growing the hydrogen market, among other steps.

Many climate experts and activists harbour great hopes that a close cooperation between China and the EU on emissions reductions could result in more ambitious Chinese commitments, which would likely result in a massive boost for China’s green hydrogen ambitions.

At the bilateral EU-China summit at the end of June, China and the EU both committed to develop economic stimuli that address both the economic and the climate crisis via a closer partnership on climate action and the energy transition – a step hailed as an “important signal to the world” by climate activists CAN Europe.

Nis Grünberg, of the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS), told Clean Energy Wire that climate change mitigation should be a rare bright spot in an otherwise contentious relationship. “Climate change is actually one of the very few topics remaining where the European Union and China have an alignment of interests,” Grünberg said. “It’s a pity that it’s been pushed down the agenda by the [coronavirus] crisis, but that doesn’t mean it’s gone away. It could be used to kickstart a more productive dialogue.”

Green hydrogen also offers opportunities for cooperation between EU countries and China, regardless of the commercial rivalry. Germany has already initiated an exchange focused on the energy transition and is confident it will now be intensified. “The National Hydrogen Strategy envisages as a priority that Germany will establish and intensify international cooperation and partnerships around the topic of hydrogen,” the country’s economy ministry told Clean Energy Wire. “An energy partnership with China has already existed since 2007, in which cooperation on hydrogen technologies also plays a role and will play an even greater role in the future.”

Europe’s hydrogen industry also stresses the crucial role of international cooperation. “Our vision is for hydrogen to develop into a globally traded commodity,” said Hydrogen Europe’s Chatzimarkakis. “The EU wants to create a hydrogen market, but hydrogen won’t ever become a real commodity if it’s just an internal EU thing,” he explained. “For some applications, going alone would make it impossible to achieve anything of note – case in point: the shipping sector, especially for deep sea shipping. It is just impossible for liquid hydrogen to be a viable option for intercontinental containerships when the possibility to refuel it will exist only in the EU,” he said, adding the same was true for aviation. “You absolutely need international cooperation for that.”