Clean Energy Wire: What do you consider the strengths and weaknesses of the German hydrogen strategy?

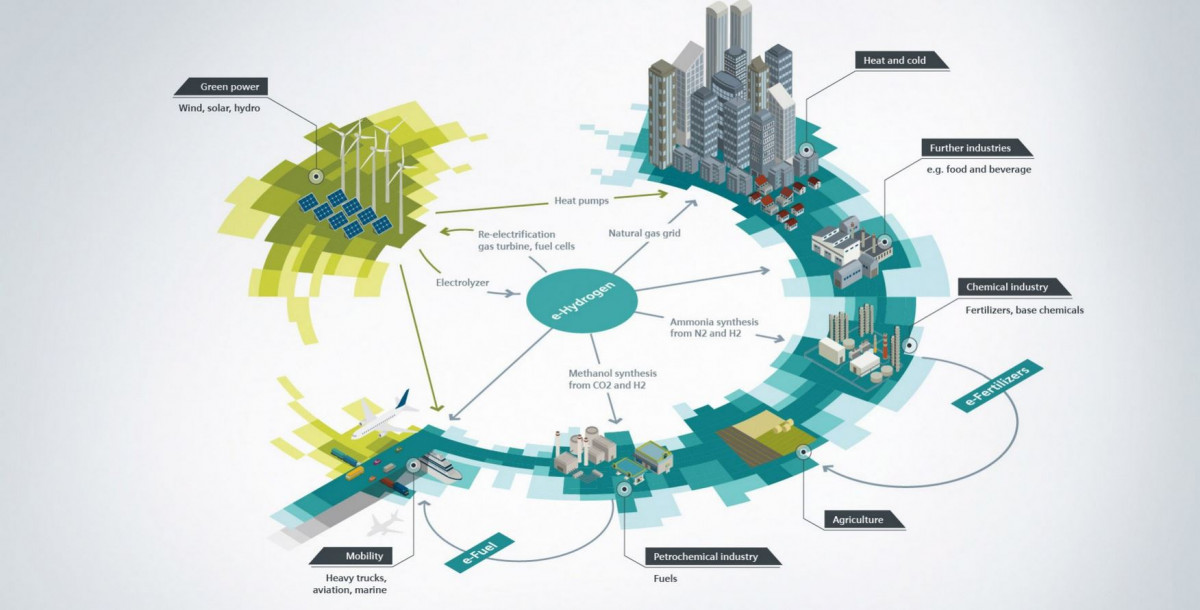

Veronika Grimm: For a start, it’s very positive that the strategy deals with hydrogen in a very comprehensive way – it considers many aspects and clearly takes industry policy issues very seriously. This is also revealed by the fact that four different ministries were involved. This issue might have delayed the strategy, but as a consequence the strategy addresses the whole value chain of a hydrogen economy: hydrogen production, logistics, and utilisation. It also clearly focusses on the industrial production of key components, from electrolysers and fuel cells to new materials and mechanical engineering. But a lot will depend on the implementation of the strategy.

When it comes to implementation, there are different ways to get the hydrogen economy going – market-oriented mechanisms, in particular uniform European CO2 prices across all sectors are important. Moreover, the reduction of taxes and levies on energy is crucial, and we have a bewildering array in Germany. Almost one-third of the electricity price consists of government-induced taxes and levies, which do not differentiate whether the electricity was generated from renewable energy sources or fossil fuels. The same applies to fuels, where energy taxes are also levied on climate-neutral fuels. As regards green hydrogen and other synthetic energy carriers, this is problematic because climate neutrality is not reflected in financial advantage. Moreover, the more expensive the power is, due to taxes and levies, the more expensive sectoral integration – that is, the use of renewable electricity to defossilise mobility, heating and industry – will be.

Making renewable power cheaper would be a huge boost for all business models that involve sector coupling. This insight can be seen in the strategy, but it is a little bit patchy. For example, the plan is to do away with the renewable power surcharge when power is used for electrolysis. But this approach is too selective. I would have hoped for a more general reform. With a rigorous CO2-oriented reform of energy pricing, many specific support programmes would be unnecessary because investments would happen automatically once cheaper power makes them economical. We should be careful not to spend too much on fragmented support and instead change the framework conditions.

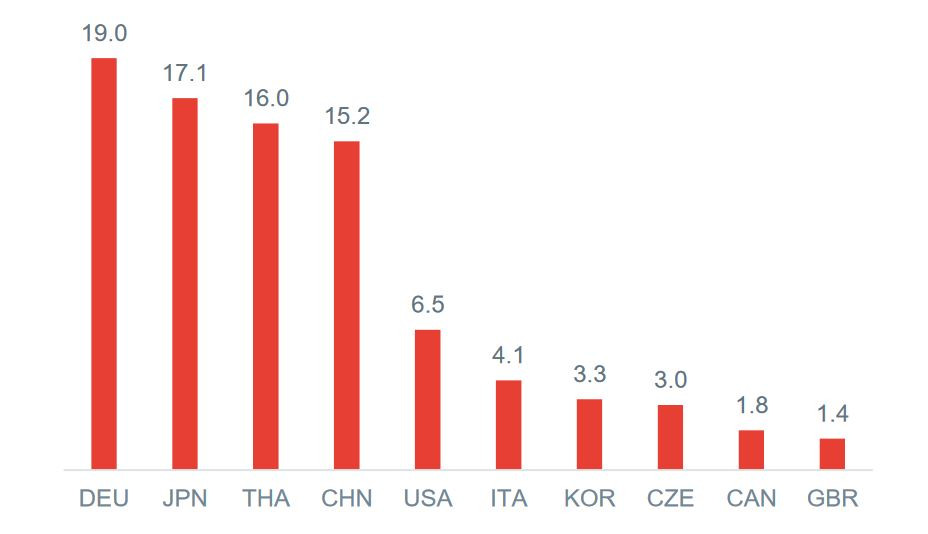

Yes, I believe the money is well spent It’s very important to create, on an ambitious timeline, the energy policy framework conditions that make hydrogen-related investments attractive for European companies. It will be decisive to support targeted research and development, but also to facilitate technology transfer from research into applications. We have to shorten the time it takes to get an innovation from the laboratory to industrial products. We also have to build up research capacities in areas that are decisive for industrial value chains. In general, we are in a very strong position in Germany and Europe when it comes to hydrogen and synthetic fuels, and we should keep that advantage. There are a number of countries around the globe that have already taken action for quite some time, for example Japan and South Korea, and many others that have now discovered this topic and are trying to catch up.

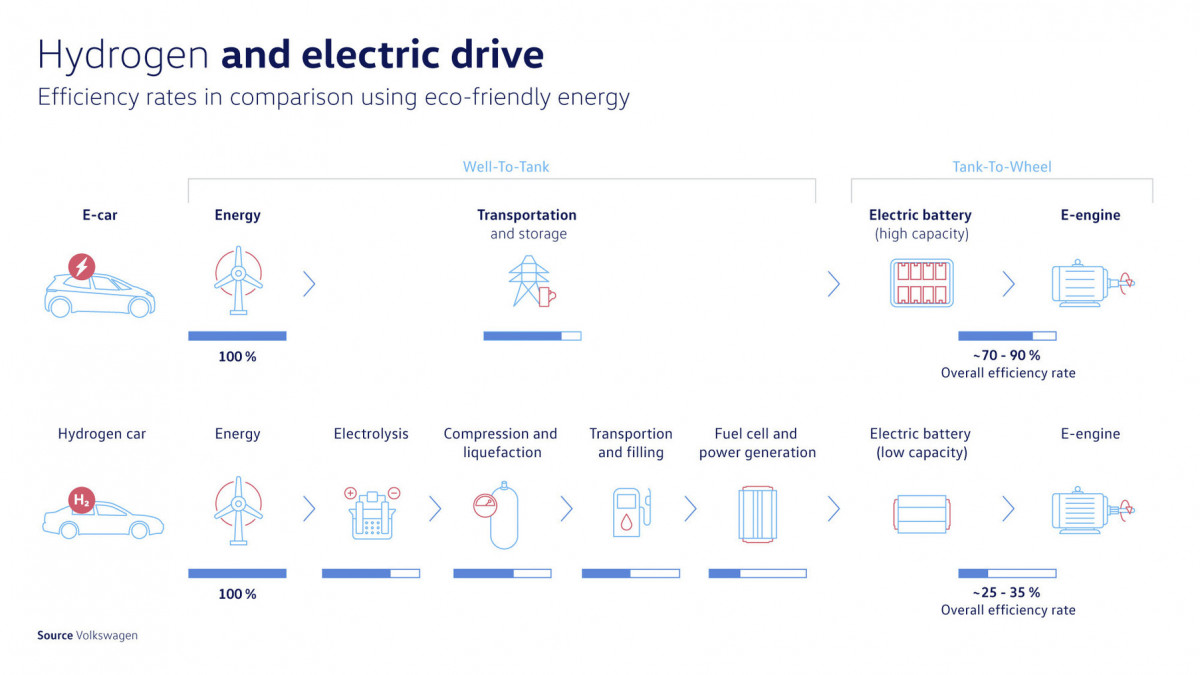

There are still many different viewpoints on various aspects of hydrogen. For example, there is the question of whether hydrogen will remain a scarce resource and should only be used where no alternatives exist, because direct electrification is not possible, or whether we move into a direction where hydrogen will be extensively traded on a global scale, and therefore will no longer be scarce. In this scenario, consumers could decide in many areas if they want to use hydrogen-based technologies, or purely power-based alternatives such as batteries.

Are you referring to fuel cell cars?

Yes, that is the obvious example and the question remains where to draw the line. It doesn’t look very likely that we will have battery-powered trucks, and given the current direction of discussions, I also believe it is highly unlikely that we will end up electrifying large parts of our highways with overhead cables. So there will likely be a heavy duty vehicle segment where hydrogen will be dominant. This means that we will need a hydrogen refuelling infrastructure for heavy duty transport anyway. In such a scenario it is very likely that markets and consumer preferences will determine whether people opt for hydrogen in other mobility segments too. I suspect this will be the case since the requirements of different users for their vehicles are very different. I think we will – and should – move toward a scenario where green hydrogen is not a scarce resource in the long run, and where consumers freely choose between various options for their mobility requirements based on their preferences. A lot will depend on the extent to which we prepare the import of hydrogen, for example through energy partnerships.

Both the German and the European strategy put quite a lot of emphasis on importing hydrogen from other countries.

Yes, exactly, and I think this is the right approach. In Germany, for example, we import 72 percent of our primary energy today in the form of fossil energy carriers. In a climate neutral world we have no choice but importing renewable energy carriers, that is green hydrogen or synthetic fuels based on it. This illustrates that we should not misjudge the amount of money that will be required to really get a hydrogen economy going. The strategies anticipate that a lot of public money will be spent on this, but it won’t be enough by a long shot. It’s totally essential to get companies on board. This is true for activities in other countries, but also domestically. Public money can certainly be a catalyst, but this can’t hide the fact that we will need massive private investments to get a hydrogen economy on its way.

Don’t you think private investors will wait on the sidelines to see if the hydrogen economy really takes off?

Not necessarily. Some people say that the coronavirus crisis will thwart the dynamics in climate policy from 2019, but on the other hand there are now good reasons to take money in hand to create perspectives for economic development post coronavirus. Even before the crisis hit, we saw a significant structural change in the German industry – for example in the automobile industry and in engineering. These developments could become even more dynamic now. Especially against the backdrop of the pandemic, it could be advisable to speed up these processes if there is money on the table to build the necessary infrastructures and so on. Many large European companies have the issue of hydrogen on the radar, and have started to go ahead.

Indeed, I am very positively surprised that these transformative topics have remained on top of the political agenda. We have at least stayed on course, if not more, and a lot of the money that will be spent to overcome the crisis will have a dual use – it will also speed up the transformation and structural change. I think this is the right approach.

Do you think the German and European strategies on hydrogen complement each other well?

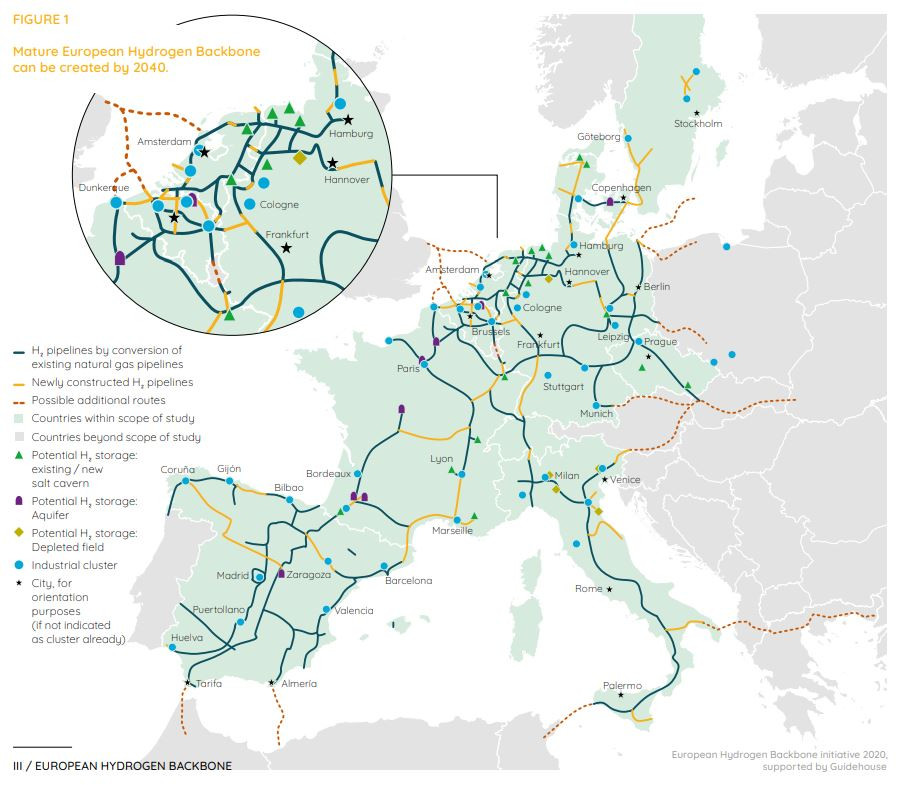

Yes, they fit together well. You can already see that many activities are starting to happen that you wouldn’t have seen otherwise. The European strategy arrived at the same time as the EU’s strategy for an integrated energy system and one of its key points is the strengthening of a European CO2 price. This is the right approach. Also, there is coordination on various levels. We have a hydrogen council in Germany that will accompany the implementation of the hydrogen strategy, and on the European level there is also a council with a strong company presence. This is good because we need to trigger private investments. You can already see that significant activities are getting underway. For example, European gas grid operators have recently presented a concept for a European hydrogen backbone. That wouldn’t have happened without these strategies.

Some people might ask whether it makes sense to step on the gas pedal to this extent, but you have to consider that these processes will take a very long time. Take the European hydrogen grid, for example. This will require intensive planning on many levels, international coordination, decisions on the regulation of the grid and its operators. It might seem hasty, but these are very time-consuming processes, so it’s important to get it started.

In Germany, this has also begun. The country’s grid agency has also presented a first assessment of what would be necessary for a hydrogen infrastructure, and what kind of regulations should be adopted. We will see a political process that will have to determine whether hydrogen will be subject to similar regulations as the natural gas infrastructure, or whether this could be run on a competitive basis given that various logistic infrastructures may probably compete. Hydrogen will not necessarily have to be transported in a pipeline system, but could also be moved using ships, trains or trucks. These discussions are taking place now and they are becoming more extensive, which is a good development.

You mentioned earlier that Europe is in a good position regarding hydrogen technologies and will have to ensure it stays ahead. Who are the most important competitors in global markets?

In Japan and South Korea a lot is happening in mobility and also in logistics. Japan has initiated large pilot projects dedicated to practicing the long-distant transport of hydrogen, for example from Australia. In certain US states, there are leading activities, and also in Canada, where this technology was developed strategically early on. In China, there are also comprehensive activities because Chinese industry has traditionally been a strong hydrogen user. Since 2010 China has also been the largest hydrogen producer worldwide, but on the basis of fossil fuels. China has, however, recognised that there is a great potential in climate neutral hydrogen, and if the country decides to decarbonise to a large extent, there is a strong will to build up the corresponding industries fast. But as far as I’m aware, the country still relies on technologies from abroad for fuel cells and electrolysers. But this may change in the future. [Please note: Our analysis Europe vies with China for clean hydrogen superpower status takes a closer look at this rivalry]

Overall, Europe is in a very good position when it comes to technological expertise, and the transition to industrial production must be the next step.

But in contrast to Japan, South Korea and China, Europe is now putting a large focus on green hydrogen.

Yes, that’s absolutely true and it is shaped by the cultural background. In Europe, one of the main motivations is to become climate-neutral, whereas Asian countries put more emphasis on opening markets for industry. Against this backdrop, it can also be an advantage from an industry point of view if you don’t differentiate between the different types of hydrogen, because you can get into the large-scale application phase much quicker. At a later stage, a key question will be who will have the strategic advantage in switching to emission-free hydrogen. In this respect, green hydrogen is not the only route to go. I think it’s highly unlikely that Germany will ever use carbon capture and storage (CCS) or carbon capture and use (CCU) – called blue hydrogen – at truly large scale, but other countries also within the EU might see this differently.

Do you still think Germany’s and Europe’s ambition to secure export markets for their hydrogen technology industries is justified?

Yes, absolutely. In other sectors, such as solar PV and in batteries, a lot of technology was developed in Germany initiated by government support, but the real cost reduction only started when China started mass production. This precedence suggests that we should take care to establish leading markets in Europe. But you can’t really compare hydrogen technologies to solar PV because these are much more systemic processes – it’s not just one module or one battery you need to produce. We have to ensure that German and European industry manages to get significant market shares. This is more likely if you translate technological competence into marketable products at an industrial scale early on.

Do you think Germany has learned from these past mistakes?

That is exactly the point. It is risky to wait and see whether these technologies stand the test of time in the markets because then it will probably be too late. If Europe acts in time, I think it’s unlikely that we will witness the wholesale transfer of hydrogen technology production to China comparable to what happened in solar PV. Because the technologies and value chains are much more complex, I believe various industries on various continents can play an important role. If we play it right and with enough ambition, we can build up competence in various areas that will lead to significant value added, for example in mobility, electrolysis, in hydrogen logistics, etc. This is about engineering and automation, but also about materials which are a strong feature in Germany’s research landscape. Therefore, there really is a lot of potential for German industry.

Do you not see a contradiction between wanting a lot of value added in Germany, but at the same time sharp cost decreases in hydrogen technologies?

Whether hydrogen technologies create a lot of value added depends on how costly CO2 emissions become in the future, either directly or indirectly, because you have to reach climate targets. If we really want to make the transition to a climate-neutral world, then all technologies have to become climate-neutral at some point and the question is which one is the cheapest. Reducing costs is a very important point, but emission neutrality is another.

You have repeatedly touched the issue of CO2 costs. Do you think it’s a realistic expectation that carbon pricing will be extended significantly in the years to come?

I believe there is a high probability that we will move in that direction, even if it won’t happen tomorrow. The European emission trading system [EU ETS] offers various windows of opportunity. The EU’s strategy for an integrated energy system explicitly named the target of harmonising emissions trading and extending it to all sectors. The next opportunity to arrive at a comprehensive system on a European level is in 2030, but many states including Germany have introduced CO2 pricing in various sectors, and there are also discussions about carbon contracts for difference. I expect the pressure to increase because it will become increasingly clear that if we want to follow that path, there is a clear trade-off between strengthening emissions trading systems and spending a huge amount of money on fragmented support schemes, which is the only alternative. If we take the climate targets really seriously they will create a lot of pressure to go via emissions trading. This makes me relatively optimistic that we will continue to move in this direction, even if it won’t happen as fast as many wish.