I flew into Unalakleet, Alaska, on a late fall day. With about 700 people, Unalakleet is large by rural Alaska standards and serves as a regional hub. The village is located on a sandy spit of land where a clear river meets the turbid water of the Bering Sea.

I flew into Unalakleet, Alaska, on a late fall day. With about 700 people, Unalakleet is large by rural Alaska standards and serves as a regional hub. The village is located on a sandy spit of land where a clear river meets the turbid water of the Bering Sea.

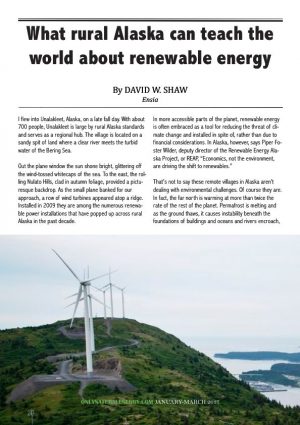

Out the plane window the sun shone bright, glittering off the wind-tossed whitecaps of the sea. To the east, the rolling Nulato Hills, clad in autumn foliage, provided a picturesque backdrop. As the small plane banked for our approach, a row of wind turbines appeared atop a ridge. Installed in 2009 they are among the numerous renewable power installations that have popped up across rural Alaska in the past decade.

In more accessible parts of the planet, renewable energy is often embraced as a tool for reducing the threat of climate change and installed in spite of, rather than due to financial considerations. In Alaska, however, says Piper Foster Wilder, deputy director of the Renewable Energy Alaska Project, or REAP, “Economics, not the environment, are driving the shift to renewables.”

That’s not to say these remote villages in Alaska aren’t dealing with environmental challenges. Of course they are. In fact, the far north is warming at more than twice the rate of the rest of the planet. Permafrost is melting and as the ground thaws, it causes instability beneath the foundations of buildings and oceans and rivers encroach, eroding shorelines. Coastal villages, once protected for much of the year by shore-fast sea ice, are increasingly exposed to storms and flooding as that ice recedes, even causing some communities to begin moving to safer, inland locations.

In that big country, the distances between the few scattered communities are daunting. If power can be generated using local renewables, the up-front cost is almost always worth it.

But, in many remote Alaskan villages, the cost of electricity is the highest in the nation, reaching a wallet-emptying US$1 per kilowatt-hour in some communities (the national average is US$0.12/kwh). The price is due to the cost of hauling fossil fuels (primarily diesel) by plane or barge to these remote areas. For example, the western half of Alaska, where Unalakleet lies, has no highways, no railroad tracks, no power lines. In that big country, the distances between the few scattered communities are daunting. If power can be generated using local renewables, the up-front cost is almost always worth it.

“We are up to 99.7 percent renewable energy,” says Lloyd Shanley, power generation manager at Kodiak Electric Association, Inc., which provides electricity to the area around the town of Kodiak (population 6,400) on Kodiak Island off the southwestern coast of the Alaska Peninsula. The primary source of KEA’s power is an alpine lake that lies in the mountains above town. With a little creative engineering, KEA ran a penstock from the lake’s steep outflow stream, channeling the water into a turbine system that contributes about 80 percent of the community’s power needs. An additional 20 percent comes from a handful of wind turbines on the ridges around town. “Our conversion to renewables has resulted in no increased cost to consumers in nearly 20 years,” Shanley says, a statistic that few communities, regardless of location, can claim.

“Kodiak should be a template,” says Wilder, but that template needs an asterisk. “The town there benefits from its topography, which allows the very successful use of small-scale hydro and wind. But every community has an abundance of some resource.”

For many villages on Alaska’s long, exposed coast, that resource is wind.

The turbines I saw from my plane window as I descended into Unalakleet have a capacity of up to 600 kilowatts of power, enough to offset the consumption of tens of thousands of gallons of diesel over the course of a year. Across Alaska, similar projects are popping up. A map of renewable power projects on the REAP website shows wind turbine icons up and down the state’s coast. Gambell, Savoonga, Nome, Wales, Shaktoolik, Emmonak, Chevak and more than a dozen other villages have embraced wind-generated power. Indeed wind turbines surrounding Alaska’s villages are so common as to no longer be remarkable.

What is remarkable is that these small, remote, economically challenged communities have successfully integrated renewable energy into their existing, diesel-based power grids with more success than just about anywhere else in the world. Remarkable indeed, and also a lesson to be applied elsewhere. Some 1.2 billion people on the planet do not currently have access to electricity. And there’s a lot these people can learn from Alaska. “Microgrids, not large-scale power generation, will be the most effective way to provide electricity to those still unconnected,” Wilder says. Microgrids are essentially small power grids customized for single communities.

In the case of rural Alaska, existing generator-based grids were modified to include renewables, but developing a microgrid from scratch makes the inclusion of renewable power sources easier.

Unlike large, centralized systems that rely on enormous power plants, microgrids provide power to small geographic areas. Ideally, their power sources, like the wind blowing across the hills of Unalakleet or Kodiak’s alpine lake, take advantage of locally abundant renewables.

Often, when people envision expanding the use of renewables to communities in need, they think of expensive solar farms, rows of wind turbines and large-scale hydro projects, but as Wilder points out, there is no one-size-fits-all solution. While she emphasizes efficiency first, other decisions depend on the community.

“The first thing we address in a community is efficiency,” she says. “Then we work on the power grid and last consider the best sources of power.” That allows the integration of renewables to take into account the resources and challenges of each community.

Every community, whether it’s an Arctic village or a small town in Bangladesh, is unique, and there are no formulaic solutions. Whether turbines spinning in the cold wind of Alaska’s coast or the precipitous streams of Kodiak, electric generation and delivery systems work best when they are adapted to the communities they serve.

David W. Shaw

Originally published

by Ensia

March 6, 2017