It’s 2025, and 800,000 tons of used high strength steel is coming up for auction.

It’s 2025, and 800,000 tons of used high strength steel is coming up for auction.

The steel made up the Keystone XL pipeline, finally completed in 2019, two years after the project launched with great fanfare after approval by the Trump administration. The pipeline was built at a cost of about $7 billion, bringing oil from the Canadian tar sands to the US, with a pit stop in the town of Baker, Montana, to pick up US crude from the Bakken formation. At its peak, it carried over 500,000 els a day for processing at refineries in Texas and Louisiana. But in 2025, no one wants the oil.

The Keystone XL will go down as the world’s last great fossil fuels infrastructure project. TransCanada, the pipeline’s operator, charged about $10 per barrel for the transportation services, which means the pipeline extension earned about $5 million per day, or $1.8 billion per year. But after shutting down less than four years into its expected 40 year operational life, it never paid back its costs. The Keystone XL closed thanks to a confluence of technologies that came together faster than anyone in the oil and gas industry had ever seen. It’s hard to blame them – the transformation of the transportation sector over the last several years has been the biggest, fastest change in the history of human civilization, causing the bankruptcy of blue chip companies like Exxon Mobil and General Motors, and directly impacting over $10 trillion in economic output.

And blame for it can be traced to a beguilingly simple, yet fatal problem: the internal combustion engine has too many moving parts.

Let’s bring this back to today: Big Oil is perhaps the most feared and respected industry in history. Oil is warming the planet – cars and trucks contribute about 15% of global fossil fuels emissions – yet this fact barely dents its use. Oil fuels the most politically volatile regions in the world, yet we’ve decided to send military aid to unstable and untrustworthy dictators, because their oil is critical to our own security. For the last century, oil has dominated our economics and our politics. Oil is power.

Yet I argue here that technology is about to undo a century of political and economic dominance by oil. Big Oil will be cut down in the next decade by a combination of smartphone apps, long-life batteries, and simpler gearing. And as is always the case with new technology, the undoing will occur far faster than anyone thought possible.

To understand why Big Oil is in far weaker a position than anyone realizes, let’s take a closer look at the lynchpin of oil’s grip on our lives: the internal combustion engine, and the modern vehicle drivetrain.

Cars are complicated.

Behind the hum of a running engine lies a carefully balanced dance between sheathed steel pistons, intermeshed gears, and spinning rods – a choreography that lasts for millions of revolutions. But millions is not enough, and as we all have experienced, these parts eventually wear, and fail. Oil caps leak. Belts fray. Transmissions seize.

To get a sense of what problems may occur, here is a list of the most common vehicle repairs from 2015:

- Replacing an oxygen sensor – $249

- Replacing a catalytic converter – $1,153

- Replacing ignition coil(s) and spark plug(s) – $390

- Tightening or replacing a fuel cap – $15

- Thermostat replacement – $210

- Replacing ignition coil(s) – $236

- Mass air flow sensor replacement – $382

- Replacing spark plug wire(s) and spark plug(s) – $331

- Replacing evaporative emissions (EVAP) purge control valve – $168

- Replacing evaporative emissions (EVAP) purging solenoid – $184

And this list raises an interesting observation: None of these failures exist in an electric vehicle.

The point has been most often driven home by Tony Seba, a Stanford professor and guru of “disruption”, who revels in pointing out that an internal combustion engine drivetrain contains about 2,000 parts, while an electric vehicle drivetrain contains about 20. All other things being equal, a system with fewer moving parts will be more reliable than a system with more moving parts.

And that rule of thumb appears to hold for cars. In 2006, the National Highway Transportation Safety Administration estimated that the average vehicle, built solely on internal combustion engines, lasted 150,000 miles. Current estimates for the lifetime today’s electric vehicles are over 500,000 miles. The ramifications of this are huge, and bear repeating. Ten years ago, when I bought my Prius, it was common for friends to ask how long the battery would last – a battery replacement at 100,000 miles would easily negate the value of improved fuel efficiency. But today there are anecdotal stories of Prius’s logging over 600,000 miles on a single battery.

The story for Teslas is unfolding similarly. Tesloop, a Tesla-centric ride-hailing company has already driven its first Model S for more 200,000 miles, and seen only an 6% loss in battery life. A battery lifetime of 1,000,000 miles may even be in reach. This increased lifetime translates directly to a lower cost of ownership: extending an EVs life by 3-4 X means an EVs capital cost, per mile, is 1/3 or 1/4 that of a gasoline-powered vehicle. Better still, the cost of switching from gasoline to electricity delivers another savings of about 1/3 to 1/4 per mile. And electric vehicles do not need oil changes, air filters, or timing belt replacements; the 200,000 mile Tesloop never even had its brakes replaced. The most significant repair cost on an electric vehicle is from worn tires.

For emphasis: The total cost of owning an electric vehicle is, over its entire life, roughly 1/4 to 1/3 the cost of a gasoline-powered vehicle. Of course, with a 500,000 mile life a car will last 40-50 years. And it seems absurd to expect a single person to own just one car in her life. But of course a person won’t own just one car. The most likely scenario is that, thanks to software, a person won’t own any.

***

Here is the problem with electric vehicle economics: A dollar today, invested into the stock market at a 7% average annual rate of return, will be worth $15 in 40 years. Another way of saying this is the value, today, of that 40th year of vehicle use is approximately 1/15th that of the first.

The consumer simply has little incentive to care whether or not a vehicle lasts 40 years. By that point the car will have outmoded technology, inefficient operation, and probably a layer of rust. No one wants their car to outlive their marriage. But that investment logic looks very different if you are driving a vehicle for a living. A New York City cab driver puts in, on average, 180 miles per shift (well within the range of a modern EV battery), or perhaps 50,000 miles per work year. At that usage rate, the same vehicle will last roughly 10 years. The economics, and the social acceptance, get better. And if the vehicle was owned by a cab company, and shared by drivers, the miles per year can perhaps double again. Now the capital is depreciated in 5 years, not 10. This is, from a company’s perspective, a perfectly normal investment horizon.

A fleet can profit from an electric vehicle in a way that an individual owner cannot. Here is a quick, top-down analysis on what it’s worth to switch to EVs: The IRS allows charges of 53.5¢ per mile in 2017, a number clearly derived for gasoline vehicles. At 1/4 the price, a fleet electric vehicle should cost only 13¢ per mile, a savings of 40¢ per mile. 40¢ per mile is not chump change – if you are a NYC cab driver putting 50,000 miles a year onto a vehicle, that’s $20,000 in savings each year. But a taxi ride in NYC today costs $2/mile; that same ride, priced at $1.60 per mile, will still cost significantly more than the 53.5¢ for driving the vehicle you already own. The most significant cost of driving is still the driver. But that, too, is about to change. Self-driving taxis are being tested this year in Pittsburgh, Phoenix, and Boston, as well as Singapore, Dubai, and Wuzhen, China.

And here is what is disruptive for Big Oil: Self-driving vehicles get to combine the capital savings from the improved lifetime of EVs, with the savings from eliminating the driver. The costs of electric self-driving cars will be so low, it will be cheaper to hail a ride than to drive the car you already own.

***

Today we view automobiles not merely as transportation, but as potent symbols of money, sex, and power. Yet cars are also fundamentally a technology. And history has told us that technologies can be disrupted in the blink of an eye. Take as an example my own 1999 job interview with the Eastman Kodak company. It did not go well.

At the end of 1998, my father had gotten me a digital camera as a present to celebrate completion of my PhD. The camera took VGA resolution pictures – about 0.3 megapixels – and saved them to floppy disks. By comparison, a conventional film camera had a nominal resolution of about 6 megapixels. When printed, my photos looked more like impressionist art than reality. However, that awful, awful camera was really easy to use. I never had to go to the store to buy film. I never had to get pictures printed. I never had to sort through a shoebox full of crappy photos. Looking at pictures became fun.

I asked my interviewer what Kodak thought of the rise of digital; she replied it was not a concern, that film would be around for decades. I looked at her like she was nuts. But she wasn’t nuts, she was just deep in the Kodak culture, a world where film had always been dominant, and always would be. This graph plots the total units sold of film cameras (grey) versus digital (blue, bars cut off). In 1998, when I got my camera, the market share of digital wasn’t even measured. It was a rounding error. By 2005, the market share of film cameras were a rounding error.

In seven years, the camera industry had flipped. The film cameras went from residing on our desks, to a sale on Craigslist, to a landfill. Kodak, a company who reached a peak market value of $30 billion in 1997, declared bankruptcy in 2012. An insurmountable giant was gone.

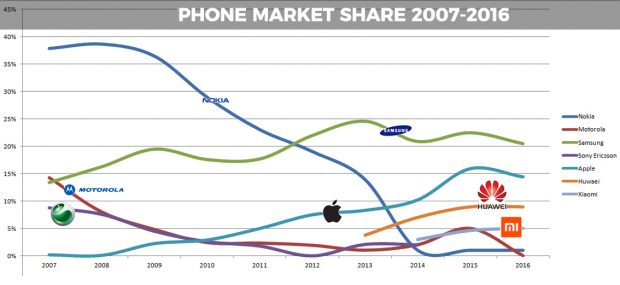

That was fast. But industries can turn even faster: In 2007, Nokia had 50% of the mobile phone market, and its market cap reached $150 billion. But that was also the year Apple introduced the first smartphone. By the summer of 2012, Nokia’s market share had dipped below 5%, and its market cap fell to just $6 billion. In less than five years, another company went from dominance to afterthought.

A summary of Nokia’s market share in cell phones. From Telephonesonline.co.uk

Big Oil believes it is different. I am less optimistic for them. An autonomous vehicle will cost about $0.13 per mile to operate, and even less as battery life improves. By comparison, your 20 miles per gallon automobile costs $0.10 per mile to refuel if gasoline is $2/gallon, and that is before paying for insurance, repairs, or parking. Add those, and the price of operating a vehicle you have already paid off shoots to $0.20 per mile, or more. And this is what will kill oil: It will cost less to hail an autonomous electric vehicle than to drive the car that you already own.

If you think this reasoning is too coarse, consider the recent analysis from the consulting company RethinkX (run by the aforementioned Tony Seba), which built a much more detailed, sophisticated model to explicitly analyze the future costs of autonomous vehicles. Here is a sampling of what they predict:

- Self-driving cars will launch around 2021

- A private ride will be priced at 16¢ per mile, falling to 10¢ over time.

- A shared ride will be priced at 5¢ per mile, falling to 3¢ over time.

- By 2022, oil use will have peaked

- By 2023, used car prices will crash as people give up their vehicles. New car sales for individuals will drop to nearly zero.

- By 2030, gasoline use for cars will have dropped to near zero, and total crude oil use will have dropped by 30% compared to today.

The driver behind all this is simple: Given a choice, people will select the cheaper option.

Your initial reaction may be to believe that cars are somehow different – they are built into the fabric of our culture. But consider how people have proven more than happy to sell seemingly unyielding parts of their culture for far less money. Think about how long a beloved mom and pop store lasts after Walmart moves into town, or how hard we try to “Buy American” when a cheaper option from China emerges.

And autonomous vehicles will not only be cheaper, but more convenient as well – there is no need to focus on driving, there will be fewer accidents, and no need to circle the lot for parking. And your garage suddenly becomes a sunroom.

For the moment, let’s make the assumption that the RethinkX team has their analysis right (and I broadly agree[1]): Self-driving EVs will be approved worldwide starting around 2021, and adoption will occur in less than a decade.

How screwed is Big Oil?

****

Perhaps the metaphors with film camera or cell phones are stretched. Perhaps the better way to analyze oil is to consider the fate of another fossil fuel: coal.

The coal market is experiencing a shock today similar to what oil will experience in the 2020s. Below is a plot of total coal production and consumption in the US, from 2001 to today. As inexpensive natural gas has pushed coal out of the market, coal consumption has dropped roughly 25%, similar to the 30% drop that RethinkX anticipates for oil. And it happened in just a decade.

Coal production

Coal consumption has dropped 25% from its peak. From the Kleinman Center for Energy Policy. The result is not pretty. The major coal companies, who all borrowed to finance capital improvements while times were good, were caught unaware. As coal prices crashed, their loan payments became a larger and larger part of their balance sheets; while the coal companies could continue to pay for operations, they could not pay their creditors. The four largest coal producers lost 99.9% of their market value over the last 6 years. Today, over half of coal is being mined by companies in some form of bankruptcy.

Coal market cap

The four largest coal companies had a combined market value of approximately zero in 2016. This image is one element of a larger graphic on the collapse of coal from Visual Capitalist. When self-driving cars are released, consumption of oil will similarly collapse.

Oil drilling will cease, as existing fields become sufficient to meet demand. Refiners, whose huge capital investments are dedicated to producing gasoline for automobiles, will write off their loans, and many will go under entirely. Even some pipeline operators, historically the most profitable portion of the oil business, will be challenged as high cost supply such as the Canadian tar sands stop producing.

A decade from now, many investors in oil may be wiped out. Oil will still be in widespread use, even under this scenario – applications such as road tarring are not as amenable to disruption by software. But much of today’s oil drilling, transport, and refining infrastructure will be redundant, or ill-fit to handle the heavier oils needed for powering ships, heating buildings, or making asphalt. And like today’s coal companies, oil companies like TransCanada may have no money left to clean up the mess they’ve left.

***

Of course, it would be better for the environment, investors, and society if oil companies curtailed their investing today, in preparation for the long winter ahead. Belief in global warming or the risks of oil spills is no longer needed to oppose oil projects – oil infrastructure like the Keystone XL will become a stranded asset before it can ever return its investment. Unless we have the wisdom not to build it.

The battle over oil has historically been a personal battle – a skirmish between tribes over politics and morality, over how we define ourselves and our future. But the battle over self-driving cars will be fought on a different front. It will be about reliability, efficiency, and cost. And for the first time, Big Oil will be on the weaker side.

Within just a few years, Big Oil will stagger and start to fall. For anyone who feels uneasy about this, I want to emphasize that this prediction isn’t driven by environmental righteousness or some left-leaning fantasy. It’s nothing personal. It’s just business.

1 Thinking about how fast a technology will flip is worth another post on its own. Suffice it to say that the key issues are (1) how big is the improvement?, and (2) is there a channel to market already established? The improvement in this case is a drop in cost of >2X – that’s pretty large. And the channel to market – smartphones – is already deployed. As of a year ago, 15% of Americans had hailed a ride using an app, so there is a small barrier to entry as people learn this new behavior, but certainly no larger than the barrier to smartphone adoption was in 2007. So as I said, I broadly believe that the roll-out will occur in about a decade. But any more detail would require an entirely new post

Originally published

by Perspicacity.xyz

May 24, 2018