“I thought fossil fuel firms could change. I was wrong.” Christiana Figueres, the former Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, wrote recently for Al Jazeera. “I was convinced the global economy could not be decarbonised without their constructive participation and I was therefore willing to support the transformation of their business model. But what the industry is doing with its unprecedented profits over the past 12 months has changed my mind.”

“I thought fossil fuel firms could change. I was wrong.” Christiana Figueres, the former Secretary of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, wrote recently for Al Jazeera. “I was convinced the global economy could not be decarbonised without their constructive participation and I was therefore willing to support the transformation of their business model. But what the industry is doing with its unprecedented profits over the past 12 months has changed my mind.”

The year 2022 was a hugely gratifying period for oil companies. $55.7bn in annual profit for Exxon; Chevron had a record $36.5bn gain; $27.7bn for BP and $39.9bn for Shell – the best results of its 115-year history. In parallel, CO2 emissions kept rising. And it’s difficult not to relate it to increasing investment in fossil fuels. A report released by research group Oil Change International found that French oil giant TotalEnergies used its record 2022 profits ($36.2bn) to double its commitment to fossil fuels. No surprise. The scale of these profits are too large to stimulate a change of policy. Any company will only abandon this golden route if forced to do so.

This route might be paved with gold but only for an exclusive minority. Many more are the excluded who are paying the price for this excess. In May, the carbon dioxide levels measured at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Mauna Loa Atmospheric Baseline Observatory peaked at 424 parts per million, an annual increase of 3.0 ppm. Two months later, on July 3, the world experienced the hottest day ever recorded, according to the United States National Center for Environmental Prediction data. This record is likely to be broken before you finish reading this article.

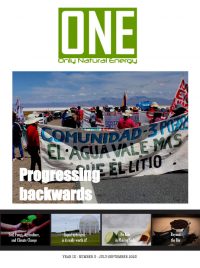

The supposed antidote is green tech based on renewable energy sources and increased electrification. But they are not issues-free: there is a mismatch between generation and timing of peak consumption; more land is required when less land is available; wind turbines, solar panels, and electric car batteries need the still mysterious but increasingly popular rare earths (the seventeen metallic elements essential to many high-tech devices) and other critical minerals such as copper, nickel, cobalt and lithium. According to the International Energy Agency’s first annual Critical Minerals Market Review, the market for these minerals has doubled over the past five years. From 2017 to 2022, the energy sector was the main factor behind a tripling of overall lithium demand. More than 75 per cent of the world’s lithium supply lies beneath Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia – the so-called ‘Lithium Triangle’. Salar de Uyuni (Bolivia) or Jujuy (Argentina) are some of the targets of the race for extraction. Still, they have also become symbolic names of the unfair transition, whereby the local populations pay the price and do not have the benefits of the work and exploitation of the resources beneath their feet. A fraud scheme that has a history and goes beyond Latin America.

Africa has been the continent most deprived of its natural resources. Over two centuries of ruthless exploitation has denuded many African countries of their natural resources, leaving them among the poorest in the world and still underdeveloped. Resources alone cannot guarantee prosperity.

Namibia has significant lithium deposits but also dysprosium and terbium, rare earth minerals needed in the batteries of electric cars and wind turbines. Recently, the national government has banned the export of unprocessed lithium and other critical minerals to profit without intermediaries from the increasing global demand for metals used in clean energy technologies. Oil companies, Figueres and Namibia hint at the actual battle at the core of the energy transition: the preservation of the status quo versus a change of attitude and unprecedented policies. Retrograde versus progress, that is the game.

Gianni Serra