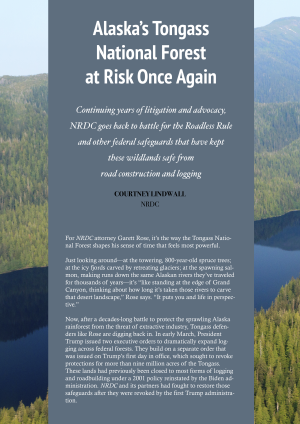

Continuing years of litigation and advocacy, NRDC goes back to battle for the Roadless Rule and other federal safeguards that have kept these wildlands safe from road construction and logging.

Continuing years of litigation and advocacy, NRDC goes back to battle for the Roadless Rule and other federal safeguards that have kept these wildlands safe from road construction and logging.

For NRDC attorney Garett Rose, it’s the way the Tongass National Forest shapes his sense of time that feels most powerful.

Just looking around—at the towering, 800-year-old spruce trees; at the icy fjords carved by retreating glaciers; at the spawning salmon, making runs down the same Alaskan rivers they’ve traveled for thousands of years—it’s “like standing at the edge of Grand Canyon, thinking about how long it’s taken those rivers to carve that desert landscape,” Rose says. “It puts you and life in perspective.”

Now, after a decades-long battle to protect the sprawling Alaska rainforest from the threat of extractive industry, Tongass defenders like Rose are digging back in. In June, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced it would rescind the 2001 Roadless Rule, a provision that generally prohibits commercial logging and road construction on 58.5 million acres across the National Forest System. The impacts will only add to the development pressure on the Tongass, following a pair of executive orders President Trump issued in March to dramatically expand logging across federal forests. These lands had previously been closed to most forms of logging and roadbuilding under a 2001 policy reinstated by the Biden administration. NRDC and its partners had fought to restore those safeguards after they were revoked by the first Trump administration.

Under the pretense of enhancing national security—and just after former timber industry executive Tom Schultz took the helm of the U.S. Forest Service—Trump’s new policies aim to supercharge the destruction of our public lands.

The stakes for the Tongass are high. Ramping up logging here will permanently harm America’s largest intact old-growth forests. It will pollute watersheds and degrade wildlife habitat. It will harm Indigenous communities that rely on the Tongass’s intact natural values. It will also undermine the region’s vibrant fishing and tourism economy.

On top of all that, the government’s latest actions come at a time when depleted and demoralized agencies are increasingly unable to fulfill their conservation mandates, making the work of protecting critical landscapes like this one even harder.

“These policy moves are trying to take us back to the bad old days of maximum logging with minimum oversight,” Rose says.

NRDC is gearing up once again alongside our coalition partners to fight these reckless moves. “Our federal forests belong to all of us and are required by law to be managed in ways that benefit all Americans,” wrote the signatories of a statement from the Climate Forests Coalition, which NRDC co-leads.

Indeed, many of the provisions in the executive orders are likely unlawful. For example, the administration is trying to apply the Endangered Species Act’s emergency provisions to regularly planned logging, inconsistent with the statute’s intent. And Trump’s direction that federal agencies rescind regulations creating an “undue burden” on logging may violate laws providing for rational decision-making and public comment.

Why protections for U.S. forests are necessary

In the early 1990s, NRDC advocates began making the case to put large portions of U.S. Forest Service lands off-limits to logging and other destructive industries. By that time, more than half of the agency’s lands had been sliced up by roads and compromised by development, leaving little room for actual wilderness. Roads, NRDC experts knew, quite literally cleared the way for extractive activities like logging and drilling, and themselves caused erosion, pollution, and disruption to wildlife. Stop the roadbuilding, and you could stem the damage.

The advocacy took the form of support for national Roadless Rule protections, and NRDC centered our efforts around the unparalleled Tongass National Forest.

The threat of road expansion there was—and still is—an obvious vulnerability for a wilderness that stretches across nearly 17 million acres of southeastern Alaska and remains the heart of the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest. The Tongass stores more carbon per acre than almost any other forest on the planet. Its centuries-old trees, alpine meadows, and streams provide habitat for more than 400 species, including Alexander Archipelago wolves (found only in southeastern Alaska), brown and black bears, bald eagles, and all five species of Pacific salmon.

“A Roadless Rule that excluded the Tongass was not a nearly big enough win for the environment,” says former director of NRDC’s Alaska Program and attorney Niel Lawrence, a longtime leader of the Tongass advocacy.

Nor was the exclusion good for its people. For millennia, these rich natural resources have also supported the Native Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian people, who rely on their ancestral homelands for food, medicine, and traditional customs.

So momentum grew for a national roadbuilding ban that could protect the Tongass, as well as millions of acres of other U.S. forests in the Lower 48, from unchecked development.

In 1999, the Forest Service instituted a temporary roadbuilding moratorium for more than 100 national forests. Soon after that, Lawrence wrote a memo to the agency outlining why the moratorium should be made permanent and extended nationwide, as well as why it should ban commercial logging. After holding more than 600 public hearings and receiving more than one million public comments, President Bill Clinton’s secretary of agriculture signed off on the Roadless Area Conservation Rule in January 2001. It was a landmark moment for American forests.

“NRDC is built to do things like the Roadless Rule—those big, sweeping changes that fundamentally reshape the legal landscape to advance environmental protections,” Rose says. “And part of that is being there after the ink is dry to keep defending them from attacks that inevitably come.”

Unfortunately, those attacks came quickly.

Defending the Roadless Rule

Just days after its passage, timber and energy interests, backed by their allies in certain state governments, tried to stop the law from going into effect. When the Bush administration took office, it attempted to delay the rule’s implementation and later proposed a do-nothing alternative that would allow states to opt out. It also approved an exemption of the Tongass from the Roadless Rule altogether—the first of multiple attempts to hand the Tongass over to industry.

But throughout, NRDC and its allies stood guard, repeatedly going to court against those who attacked the Roadless Rule. Thanks to the solid science and years of analysis underpinning the Roadless Rule, it held firm, and the attempts to exempt the Tongass were thrown out by the courts.

That is, until another environmentally unfriendly administration took up the crusade.

The first Trump administration brought with it a tsunami of environmental rollbacks. Despite the fact that the logging industry had largely left southeastern Alaska by this point, it was the president himself who instructed the Forest Service to exempt the Tongass in 2020, and now, once again, in 2025. “I think he understood that, for his base in Alaska, bashing the federal government for ‘locking up natural resources’ that they see as their birthright to exploit is great sport and really, very good politics,” Lawrence says.

But those in southeastern Alaska—who relied on the region’s billion-dollar tourism, recreation, and commercial fishing industries—strongly disagreed. More than 95 percent of public comments, which included nearly 40,000 signatures from NRDC members, opposed the Tongass exemption in 2020. When the administration ignored the feedback and finalized the rule anyway, NRDC, alongside Earthjustice and representing a number of allied Indigenous and other groups, took the agency to court.

Strategy again shifted when the Biden administration came into office, bringing a commitment to climate action and a dedication to center Indigenous communities—like southeastern Alaska’s Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian peoples—who stood to be most impacted by ill-considered projects.

“The administration reached out to tribes in southeast Alaska, listened to what they said, and prioritized their interest in this land that they’ve lived on for many thousands of years in a way that no administration, Democratic or otherwise, had done,” Lawrence says. “I think it stands as a watershed moment for how the federal government approaches decision-making with existential consequences for Indigenous groups.”

Once again, NRDC staff and members built momentum, submitting public comments and getting in front of policymakers to demand a full reinstatement of the Roadless Rule. The advocacy paid off when, in January 2023, the Forest Service restored full protections for nine million acres of the Tongass. And, thankfully, no development happened in the interim when the Roadless Rule was not in effect.

“The restoration…is a great first step in honoring the voices of the many tribal governments and tribal citizens who spoke out in favor of Roadless Rule protections for the Tongass,” Naawéiyaa Tagaban, environmental justice strategy lead for Native Movement, said in a statement issued at the time.

A strong and persistent Tongass alliance regroups

Environmental advocates and local businesses alike are determined not to let these lands meet the same fate of so much of the nation’s old-growth forests. Southeast Alaska welcomes millions of tourists each year, who come primarily to experience the region’s stunning natural expanses. According to an annual report on the region’s economy issued by the business-focused Southeast Conference, tourism is the top job provider, encompassing 8,300 jobs and nearly $350 million in earnings for the sector in 2024.

As cruise season got underway this spring, many in the industry were worrying about the impacts that this logging-focused policy agenda and the rash of federal workforce cuts will have on the Alaska visitor experience—and the state’s economic future. Juneau-based tourism representatives recently told the Anchorage Daily News that virtually all the employees at the Mendenhall Glacier Visitor Center, part of the Tongass National Forest, have been terminated. Some 700,000 visitors typically descend on the site annually.

With Tongass a centerpiece of Alaska’s eco-travel economy, a climate powerhouse, and a vital resource for the communities who have stewarded the forest for millennia, its ability to withstand the whims of political adversaries has depended on the resolve of a diverse community of advocates. “Would we have gotten this far without the action of a coalition? Absolutely not,” Rose says.

[These places are only] “protected because there’s a dedicated group of folks who are willing to stand there and keep fighting,” he adds. “Year after year after year.”

Courtney Lindwall

Originally published

by NRDC

April 8, 2025