Most of the world’s countries support these global agreements on conservation and pollution, but the United States is noticeably absent.

In one of his first acts in the White House, President Joe Biden signed an executive order to have the United States rejoin the Paris climate agreement. It signaled an important step in the country recommitting to action to tackle climate change after the Trump administration withdrew the United States from the accord and worked to roll back environmental regulations nationwide.

Biden’s move was hailed by world leaders and applauded by environmentalists at home. But the climate convention wasn’t the only global environmental agreement from which the country has been conspicuously absent.

Here are four international treaties that have been ratified by most of the world’s countries, but not the United States.

1. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

The 1982 Law of the Sea helped set an international framework for managing and protecting the ocean, including by delineating exclusive economic zones and creating the International Seabed Authority, which is currently tasked with drafting regulations for deep seabed mining.

“Originally the U.S. government was on board with the treaty when it was being finalized in the late 1970s, but when President Reagan came into office he called for a review of the negotiations, fired the State Department’s head of negotiations and appointed his own people who created a new list of demands,” says Kristina Gjerde, an adjunct professor at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies and a senior high seas advisor to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Global Marine and Polar Program.

When the treaty wasn’t reworked to meet those needs, Reagan’s team didn’t sign it. It would take until 1994 to get a U.S. signature, but the country still has yet to ratify it. To do so, would require a two-thirds approval in the Senate.

“The Law of the Sea has been uniformly supported by everything from the U.S. Navy to the Department of Commerce,” says Gjerde. “There’s nobody who’s really against it — other than those who don’t like the U.S. to be engaged in multilateral institutions.”

Unfortunately there are enough people in the Senate with that mindset to hold up this treaty, and many others. But that hasn’t stopped people from continuing to push for the United States to accede to the Law of the Sea.

There are numerous reasons why it would be beneficial for the country, but Gjerde says one of the most important right now is that the United States has to take a back seat while regulations are being drafted on deep seabed mining.

“The United States doesn’t have a voice in helping to make sure that the regulations are appropriately environmentally precautionary,” she says. “And the country has a lot of islands and waters that would be subject to potential environmental impacts from seabed mining by other states.”

2. The Convention on Biological Diversity

The treaty, which garnered its first signatures at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, has been called the world’s best weapon in fighting the extinction crisis. It has three main stated objectives: the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components, and the equitable sharing of benefits that arise from using genetic resources.

The United States was a big player in drafting the agreement, but when 150 nations stepped up to sign it, George W. Bush declined to do so. Bill Clinton signed the treaty after he took office in 1993, but it never received the necessary ratification vote by the Senate.

And it still hasn’t.

The United States is the only member of the United Nations that has yet to ratify it, “which is just a disgrace,” says Maria Ivanova, a professor of global governance and director of the Center for Governance and Sustainability at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

This omission stands in stark contrast to the country’s history of commitment to conservation, she says.

“The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species was initially called the Washington Convention because the first meeting was in D.C.” says Ivanova. “The United States was a champion for that convention and the first to start national parks.”

But that commitment began to fade in the 1980s with “run-amok capitalism,” she says. “That means you can use nature with impunity without replenishing anything. “

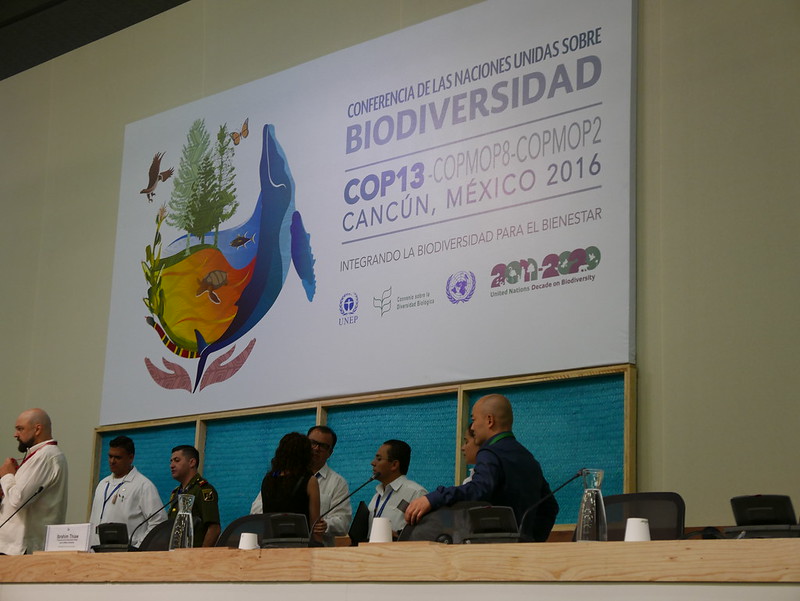

The United States does still participate in the Conference of Parties that assemble for the Convention on Biological Diversity, but without having ratified the agreement, it’s relegated to “observer” status. This year it will get some extra muscle from a California delegation that will also be attending in the hope of ramping up the United States’ commitment to biological diversity.

Conference of Parties for the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2016. Photo: Biodiversity International, (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

3. Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants

The Stockholm Convention, an effort to protect the health of people and the environment from harmful chemicals, was adopted in 2001. The treaty identifies “persistent” chemicals — those that stay in the environment for a long time and can bioaccumulate up the food chain.

Currently the treaty regulates nearly 30 of these chemicals, which can mean that countries must restrict or ban their use, limit their trade, or develop strategies to properly dispose of stockpiles or sites contaminated by the waste from the chemicals.

So far 184 countries have ratified the agreement. The United States signed it in 2001, but once again, the treaty has yet to be ratified by the Senate. That means that the United States is often behind the curve on banning harmful chemicals, such as the highly toxic pesticide pentachlorophenol.

4. Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal

The United States has also signed but not ratified the Basel Convention, which took effect in 1992. This international treaty limits the movement of hazardous waste (excluding radioactive materials) between countries. It was written to help curb the practice of richer, industrialized nations dumping their hazardous waste into less developed and less wealthy countries.

The convention is now taking on the global scourge of plastic waste, of which the United States is the largest contributor. A new provision went into effect this year that seeks to curb the amount of waste shipped to other countries that can’t be recycled and ends up instead being burned or escaping into the environment.

A pile of plastic casing for LCD screens near Sriracha, Thailand. Photo: Basel Action Network, (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The Basel Convention has also worked to address electronic waste. The failure of the United States to ratify the treaty, experts say, has allowed companies to shift recycling of toxic computer components to developing countries. Outsourcing of plastic and e-waste recycling from the U.S. to developing countries has recently been linked to chemicals entering the food chain through eggs eaten by the world’s poorest people.

Next Steps

If you’re seeing a pattern here of the United States signing — but not ratifying — treaties, you’re not wrong. “In the United States, the biggest hurdle is that ratification of a treaty has to go through the Senate,” says Ivanova.

Despite this roadblock, which has stopped the United States’ full participation in some international agreements for decades, some still hope for a different outcome. “I think it’s sort of the dream of most who are engaged in international action that the United States would join these important international processes,” says Gjerde.

When it comes to the Law of the Sea in particular, she says, “It’s an opportunity to show real, global leadership again in tackling the many challenges facing the ocean.”

There are others who might not agree.

“You hear the argument from a lot of the policymakers internationally that they’ve been doing fine without the United States in the negotiations,” says Ivanova. “So maybe it’s better that the United States doesn’t sign.”

That may be because the United States can object to a lot of things and be an obstacle as negotiations are worked out. Or because the country can negotiate from its own national interest point of view.

“The United States has disproportionate power in global governance,” she says. “Or it used to. It has to regain the credibility and the legitimacy that it lost.”

But, she says, there are likely more benefits to the United States ratifying the conventions and being a rightful actor on the world stage.

“All of these problems are global, and we need all countries engaged,” she says. “We need all hands on deck. And the United States is a powerful state and brings with it a lot of additional expertise and engagement.”

The United States, in addition to government representation, has top universities and NGOs that do research and advocacy. “And so when the United States is a part of an agreement, it brings with it all of the power that it has intellectually and financially,” says Ivanova.

Not participating leaves the country open to criticism, as well as reduces the likelihood some countries will improve their laws on their own. Most recently, the United States’ environmental shortcomings have been called out by China whenever its own record is questioned.

With this in mind, the best thing the United States can do to reestablish its environmental credibility internationally is to take action at home. The Obama administration got the narrative right, but it didn’t sufficiently match on action, Ivanova says. Now, it’s crucial to do better.

“A lot of people misunderstand the global part [of these international treaties],” she says. “You actually implement them at home — you don’t go and implement them in other states. To achieve those goals, you actually have to take action at home.”

by Tara Lohan

August 2, 2021

Originally published in The Revelator